This part of the State Museum is for the birds

State Museum curator of birds Jeremy Kirchman with a snowy owl specimen.

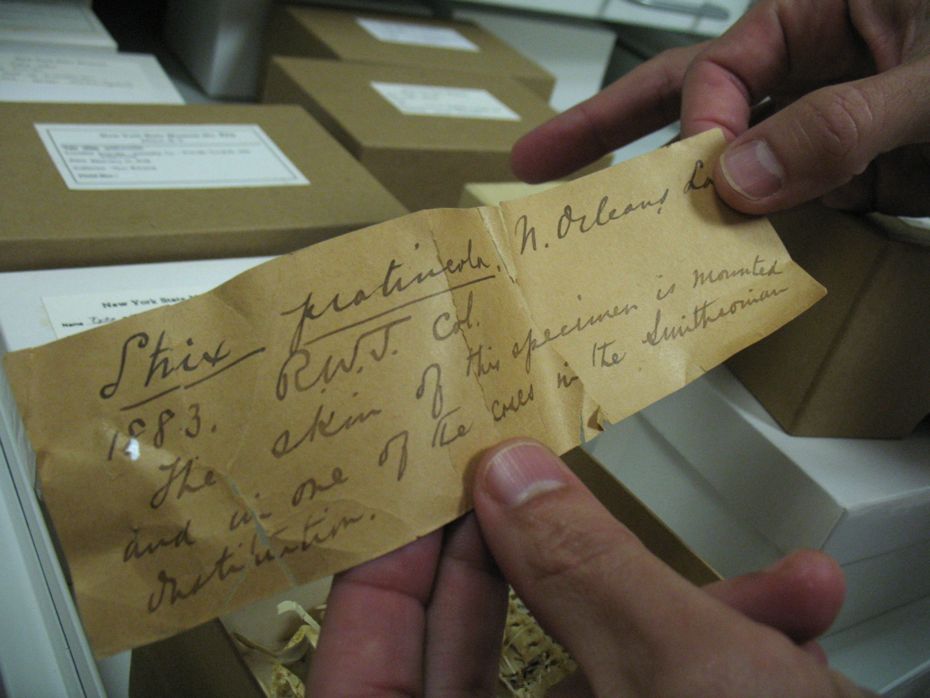

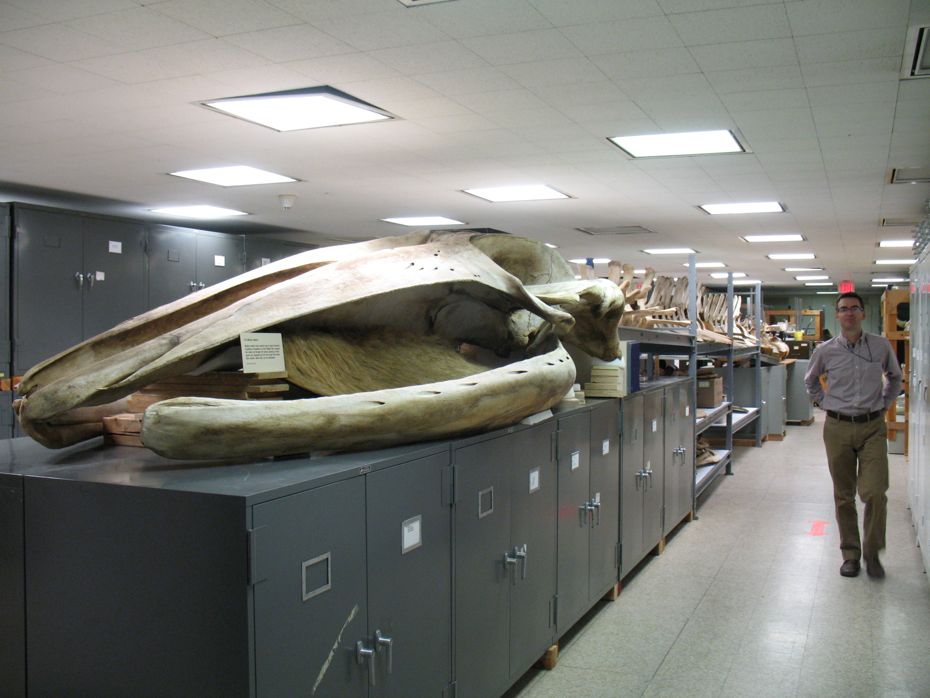

What's on display at any one time at State Museum is just small slice of all the items in the museum's collection. And because the State Museum is almost two centuries old -- it's the oldest state museum in the country -- there are a lot of things in that collection.

So we were happy to get the chance this week to get a behind-the-scenes look at the museum's large bird collection with its curator of birds, Jeremy Kirchman. He's giving a talk this Sunday about the passenger pigeon -- a current exhibit at the museum commemorates the bird's extinction a hundred years ago.

OK, let's get to the photo tour -- and a quick chat about museums as data sets, global warming, extinction, and some reasons to be hopeful.

Photo tour

It's above in large format -- click or scroll all the way up.

Interview

What are some of the questions that collection of birds here at the State Museum can help answer or address?

Well, all museum collections can be thought as a longterm data set. And in any given year, the specimens that are preserved are a snapshot of bird distributions and bird physical conditions and bird DNA. And so you can go back in time. It's the next best thing to having a time machine.

So if we wanted to answer the question "What's happening with spruce grouse in the Adirondacks?" -- we know they're rare and they're declining up there -- so one of the uses of the collection that I've done is to compare genes from birds that are alive today to blood samples taken by ecologists and compare them to genes from birds collected 100 or 150 years ago as museum specimens. And then you can say, have they always been this in-bred? How in-bred do they look now? And what is their most close relatives in terms of other populations that you might be able to use to sort of rescue this population?

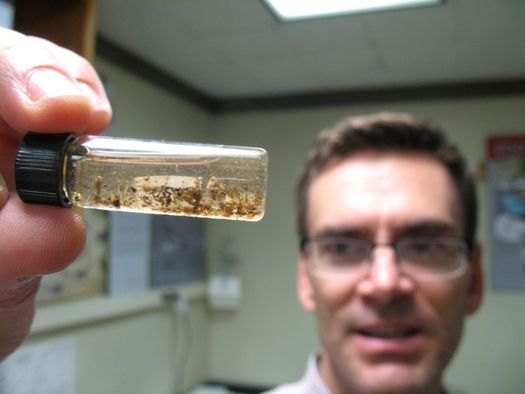

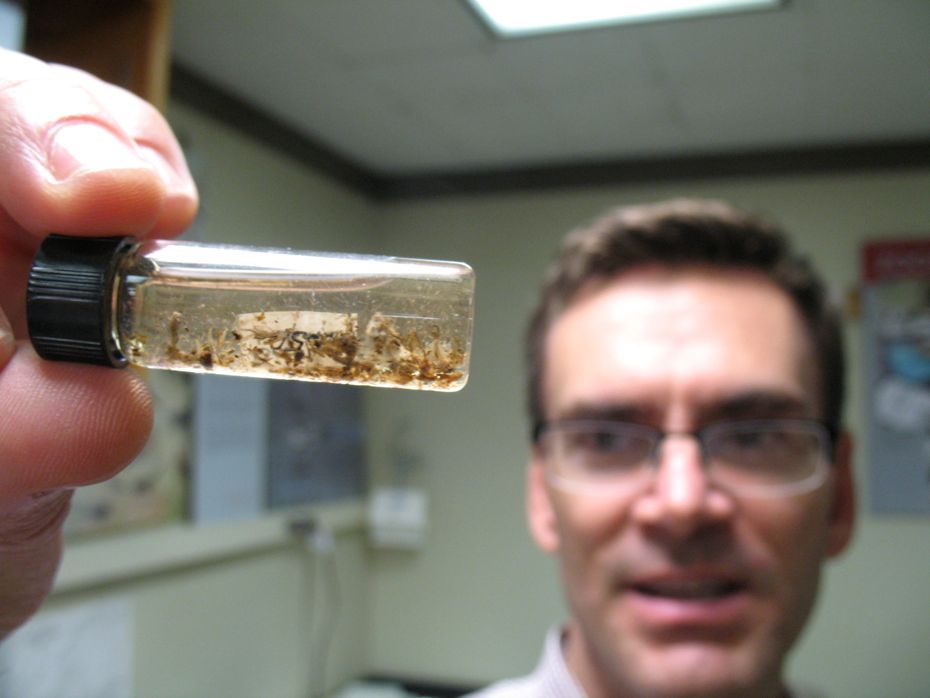

A vial of stomach contents from a bird.

So that's just one of example. But all museum collections are this way in that they're a longterm data set. And it's not just one kind of data. So when Elon Howard Eaton collected those spruce grouse near Mt. Marcy 120 years ago, he didn't know what a DNA molecule was. But now, with DNA technology, I'm able to get DNA out of those birds that he shot and compare them to birds that are alive today. And in this case generate what I think is an interesting natural history study which has to do with a decline in genetic diversity as the population approaches its extinction. So this falls into the category of academic scholarship. In that case we're learning more about the evolution of birds, but it's also useful to people over at DEC who are trying to figure out what to do about spruce grouse, whether they should augment that population or manage it differently. So museums help them out in that regard because we've managed to keep these things for so long.

The other thing about museums is that they're great teaching tools. So you can show people -- in their hand -- what an owl skull looks like. And people are amazed by that. It's inspiring to have these natural history objects.

So it's worth holding onto these collections because of the questions that we know we can answer with them, but also anticipate that there are questions in the future that we haven't even imagined yet that will be useful. And in the present they're useful as educational tools, as well.

There's been a lot of attention recently on climate change and how it's affecting species. [There was a big report from Audubon about this topic recently.] As far as birds in New York State go, as the climate changes and if it continues to change as projected, what are some of the things that are going to happen?

Some of the things we've already started to notice. So for species that are primarily southeastern [New York], we used to be on the very northern periphery of their range and now their ranges have moved well into New York even up beyond it. One of the studies I recently published was on red-bellied woodpeckers -- they used to just barely make it into the New York City area and the Lake Ontario plain around Rochester. Now they're found commonly around the whole state -- except for the Adironacks because it's a different forest type -- and all the way up to Maine. So to that list you could also add gray catbirds, Carolina wren, black vulture, and a handful of other bird species. They used to be really rare or non-existent in New York, but now they're common.

On the other end of things, we're kind of on the southern periphery of a lot of boreal forest birds that you can only find at high elevations in the Adirondacks and the Catskills. These are birds I've been studying with my graduate students -- black warblers, yellow-bellied flycatcher, Bicknell's thrush. And those of birds we're sort of nervous about losing, and we think that there's some evidence of them having moved uphill. So their lower altitudinal boundary has shifted higher, probably because of climate warming. But we haven't lost them, yet. So one of the things we're worried about is losing our Bicknell's thrushes. They'll probably be OK if they find places farther north, but you never know how that's going to go. They might not be willing to move to those places. They might be out-competed by other birds up there. In the case of Bicknell's thrush, the biggest threat is what's happening at their wintering grounds, which we have very little control over, but try to save forests in the Dominican Republican. And there are other biologists who are doing a great deal along those lines.

In terms of climate changes, these distributional shifts are what we expect to see a lot of. And we are seeing a lot of these southern birds moving north.

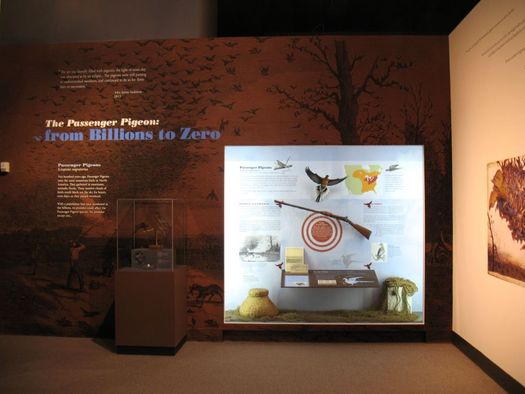

The museum's passenger pigeon exhibit.

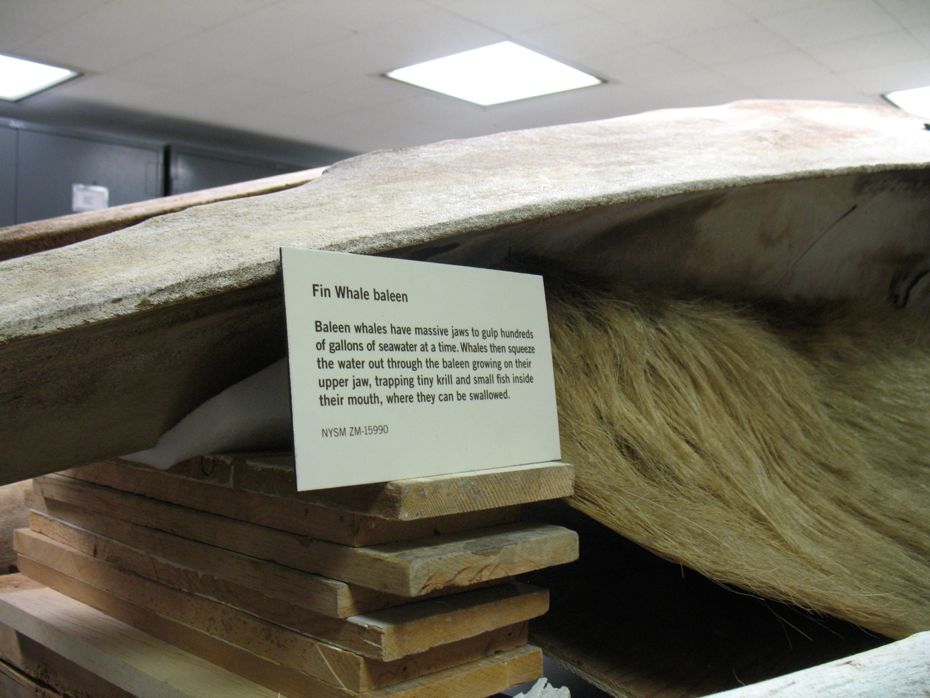

Because this is the 100th anniversary of the extinction of the passenger pigeons' extinction, what do you think the biggest lesson of the passenger pigeon story is for us?

I would say that it was shocking to learn that even a super-abundant continental species could be driven to extinction in such a small amount of time. That the human species is capable of that kind of extinction event.

It's easier to imagine how flightless birds on islands have been driven extinct. Because people showed up and ate them directly. Or people showed up and brought chickens, and rats, and dogs, and pigs. Or cats -- cats are a big problem on islands, and also on continents.

But the passenger pigeon isn't like that. It wasn't a localized or rare species. It was widespread and super abundant. It may have been the most abundant bird species in the world. And there are estimates that it may have been 25-40 percent of all North American birds before we started to really hammer them. So to think that we could take it from that to zero in one human lifetime is real eye-opener. People in the 19th century just wouldn't have imagined that they could have seen a day when there were no passenger pigeons around. And just like that -- there weren't. So you have to be careful.

Another lesson is the value of laws that protect wildlife. So that era, the 1840s to 1900, is sort of the peak for historic extinctions of birds. And since then we've lost very little -- Eskimo curlews, dusky seaside sparrows -- they go extinct in the 20th century. But most were lost in the era before laws protecting these things. But since those laws we've done a really good job of avoiding extinctions.

In the 1950s and 60s, when we started to problems with raptors, populations plummeting -- bald eagles, peregrine falcons -- museums were instrumental in helping to figure what the problem was by studying the egg shell thinning. They were able to look at these problem of eggs breaking in raptor nests, compare to the thickness of those egg shells to historic egg specimens, and say, yes, this is is the problem, this is why we don't have any more bald eagles in New York, they're not reproducing.

So through that scientific discovery they were able to say, OK, what we need to do is get rid of DDT, which was causing this. And we need to institute programs that will actively manage these populations with captive breeding and releasing birds that are trapped somewhere else. And we've brought those things back -- bald eagles are not in trouble anymore, and peregrine falcons are more numerous than they have been in the last century or so.

So I like that story because it's a story where museums have made a contribution to conservation. Because when those peregrine falcon eggs were collected in the 1890s, they didn't know that they'd be useful for figuring that problem out. And I think that's true of all the specimens that we're collecting today, that they might be useful in ways we haven't figured out, yet.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

____

Jeremy Kirchman's talk about the passenger pigeon -- "The Passenger Pigeon, Icon Of Extinction" -- is Sunday, September 28 at 1 pm in the museum's Adirondack Hall. It's free.

Hi there. Comments have been closed for this item. Still have something to say? Contact us.

Comments

This is great. But Jeremy Kirchman, *please* bring back the "Cooking the Tree of Life" series. Charge a few $$ if needed. Thanks.

... said -S on Sep 25, 2014 at 9:15 PM | link

Excellent photo tour and interview. Seeing those Ivory-Billed Woodpecker and Carolina Parakeet specimens just breaks my heart. I wish they were still around today.

... said Ellen on Sep 30, 2014 at 7:19 PM | link