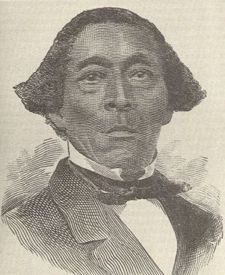

Stephen & Harriet Myers, station agents for Albany's portion of the Underground Railroad

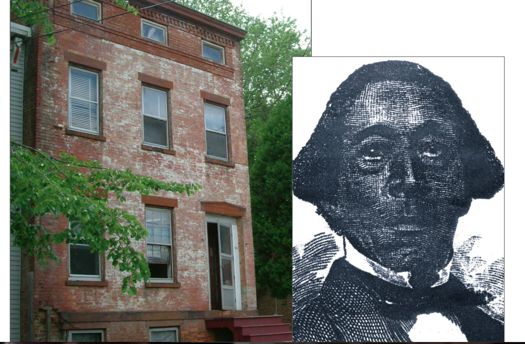

Abolitionist Stephen Myers and the Albany residence where some of his story played out.

Each Friday this February we'll be highlighting people and stories from the Capital Region in honor of Black History Month.

We live in a part of the country where history is part of the landscape. We pass historic markers on trips to the grocery store, and monuments on visits to the bank. Historic figures live on in the names of streets and cities and public buildings --- even if many no longer remember who they were, or what they did to earn the honor.

Take, for example, Stephen and Harriet Myers.

Chances are that you've driven past their former home on Livingston Avenue or the Albany middle school that bears their names, maybe without giving them a thought.

But this Capital Region couple has a remarkable, important story: The Myers played a key role in the history of the Underground Railroad in this area, helping hundreds -- possibly thousands -- of escaped slaves.

Paul Stewart -- co-founder of The Underground History Project in Albany, which is working to restore one of the Myers's former residences on Livingston Avenue (formerly 198 Lumber Street) -- says it's hard to know exactly how many people the couple helped.

"They started their efforts in the early 1830s," he points out, "and in the last few years of the 1850s alone as many as 600 people are identified."

Stephen Myers was born into slavery in Rensselaer County in the home of Johnathan Eights, an Albany physician. Freed at the age of 18, he worked at a series of jobs in the region -- a butler, a waiter, a steward, a janitor -- from Lake George down to New York City.

Stephen Myers was born into slavery in Rensselaer County in the home of Johnathan Eights, an Albany physician. Freed at the age of 18, he worked at a series of jobs in the region -- a butler, a waiter, a steward, a janitor -- from Lake George down to New York City.

In 1827 he married Harriet Johnson, whose family owned a sloop and was involved in transporting cargo between Albany and New York City. Together Harriet and Stephen Myers began their work on the Underground Railroad.

Stewart says David Ruggles, an early abolitionist leader in NYC, wrote in a letter published in one of the noted abolitionist newspapers that Myers and the Albany station were one of the most effective at aiding fugitives. And Stephen Myers earned the praise of the famous abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass.

To support his family, and his cause, Stephen Myers worked in the only jobs available to him: low-level service jobs. But he was still able to win friends, wield influence, and lobby the state legislature.

"Being in Albany was key to his success," says Paul Stewart. "Over the years he worked as a steward for some ships that went up and down the Hudson, so he had access to contacts in New York City. In Albany he worked in some of the hotels, particularly the Delavan House, a temperance hotel where many abolitionists stayed. He was headwaiter there and this gave him the opportunity to provide jobs for escaped slaves and also to interact with prominent abolitionists."

Among Myers supporters and contributors were New York governors John Alsop King, William Seward and Edward Morgan; as well as Horace Greeley from the New York Tribune and Thurlow Weed of the Albany Evening Journal.

The Myers also published a series of newspapers that Stewart says gave them access to a wide variety of people and helped maintain contacts.

"Newspapers were the social media of the day," Stewart points out. "An awful lot of people were more literate than we like to think and one of the pastimes that people took advantage of was reading to each other. So the newspapers played a great role in passing information and the general educational development."

Paul Stewart says the papers also helped Myers re-enforce connections with abolitionists and powerful people. "He became involved with colored men's conventions groups, which were intellectual groups working for the agenda of African Americans," says Stewart.

Myers worked for suffrage for African Americans, founding a suffrage club in Albany. Later he became president of the New York State Suffrage Association. He led a failed effort to strike down the $250 property requirement that applied only to black voters in the state.

Myers believed in the elevation of African Americans through education and suffrage. He also worked for economic development, becoming a trustee of the Florence Farming and Lumber Association, a farming and lumber community in Oneida, New York where the hope was that black people could live and work and earn money. The community, says Paul Stewart, was going to be "a place for people to settle, get farms make a living for themselves." It didn't work out, in part because of the soil and internal bickering, but also, says Stewart, because of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. "Many people were frightened of the law," says Stewart. "They didn't know how it was going to be implemented, so many blacks fled to Canada and that made the community collapse. What could have been an economic success was undermined by this law."

Harriet Myers died in 1865, not long after the Union army's victory in the Civil War. Stephen Myers' last job was as a janitor for a retired general running a post office branch in New York City.

"You think about a janitor and it makes you think of a lowly position," historian Paul Stewart says, "but if you think about it, the janitor is a very powerful person in some respects. They have the keys to everything. They know how everything runs."

Stephen Myers died in Albany in 1870. He is buried in Albany Rural Cemetery.

Paul and Mary Liz Stewart, founders of the Underground Railroad History Project, will speak about the Stephen and Harriet Myers House and the Underground Railroad February 11 at a luncheon at the Albany Roundtable. Tickets are $20.

photos courtesy of the Underground Railroad History Project

Hi there. Comments have been closed for this item. Still have something to say? Contact us.

Comments

This is a great highlight. It's important to note that this is not just black history, but rather it is America's history.

... said A on Feb 6, 2015 at 12:39 PM | link

Great and inspiring story. Thanks for making my day.

... said Otis Maxwell on Feb 6, 2015 at 3:38 PM | link

I love hearing these amazing stories about our little city. It gives me such pride calling this place home. Also gives me some cool facts to know on trivia night ;)

... said Melissa on Feb 9, 2015 at 10:29 AM | link

I have wondered who the Myers were, prominent enough to have a middle school after them! Thank you for this wonderful tidbit of Albany history that makes living here a little richer for the history!

... said Bonita Sanchez on Feb 9, 2015 at 11:59 AM | link

This is a great piece for Black History month, but remember history is happening everyday. Mary Liz and Paul Stewart work everyday and all year long to help bring the history of the underground railroad and the Myers and their connection to the capital region, especially Albany! I suggest going a step further than this article and find out more about the Stewart's efforts to connect us with our history plus the work they do with our youth. Thank you Albany All Over for bringing attention to Albany's Black History!

... said T on Feb 9, 2015 at 12:03 PM | link

Great story with good people telling it. All Over Albany is living up to it's name. Thank you.

... said Clifford Oliver Mealy on Feb 9, 2015 at 2:49 PM | link

Paul and Mary Liz Stewart have done and continue to do so much to promote the story of the Underground Railroad in the region. Agree that their work should be highlighted in another post!

... said Susan on Feb 11, 2015 at 12:26 PM | link