Here's a look at the big, new State Museum exhibit about the women's suffrage movement

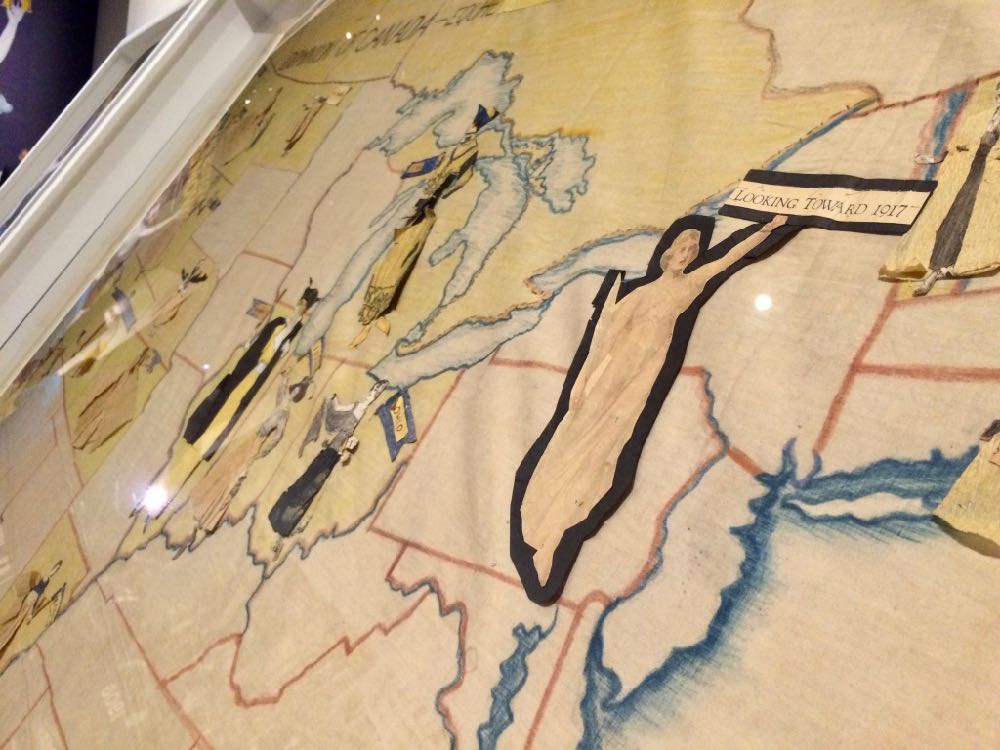

This year marks the 100th anniversary of women's suffrage in New York State. To be specific, it was November 6, 1917 that New York voted 54-46 to grant women in the state the full right to vote.

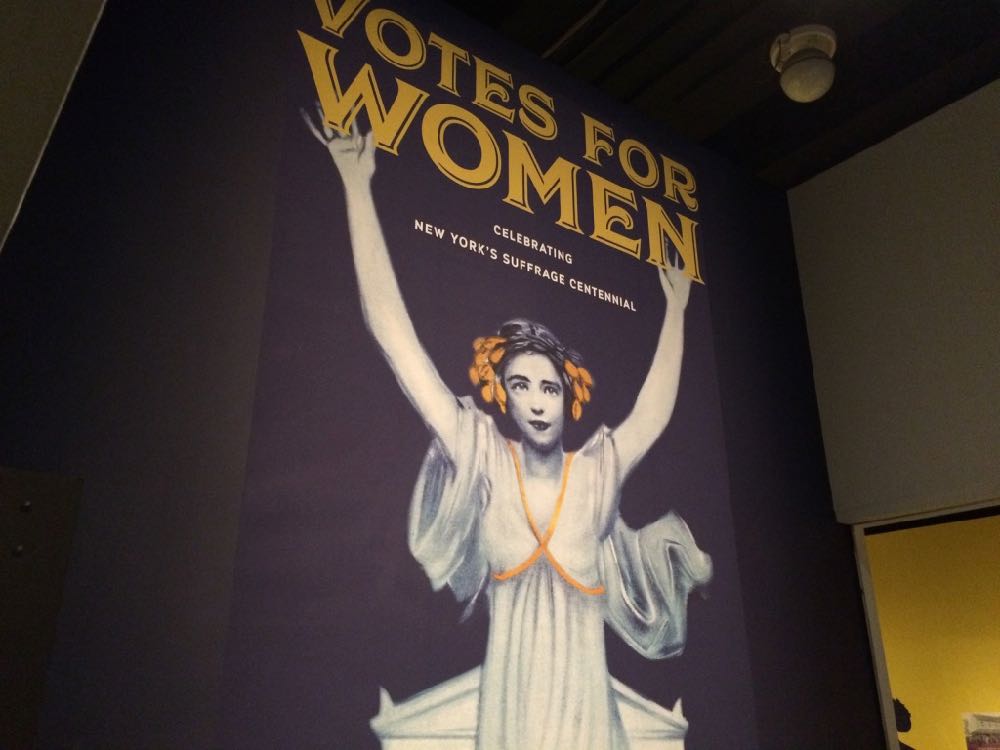

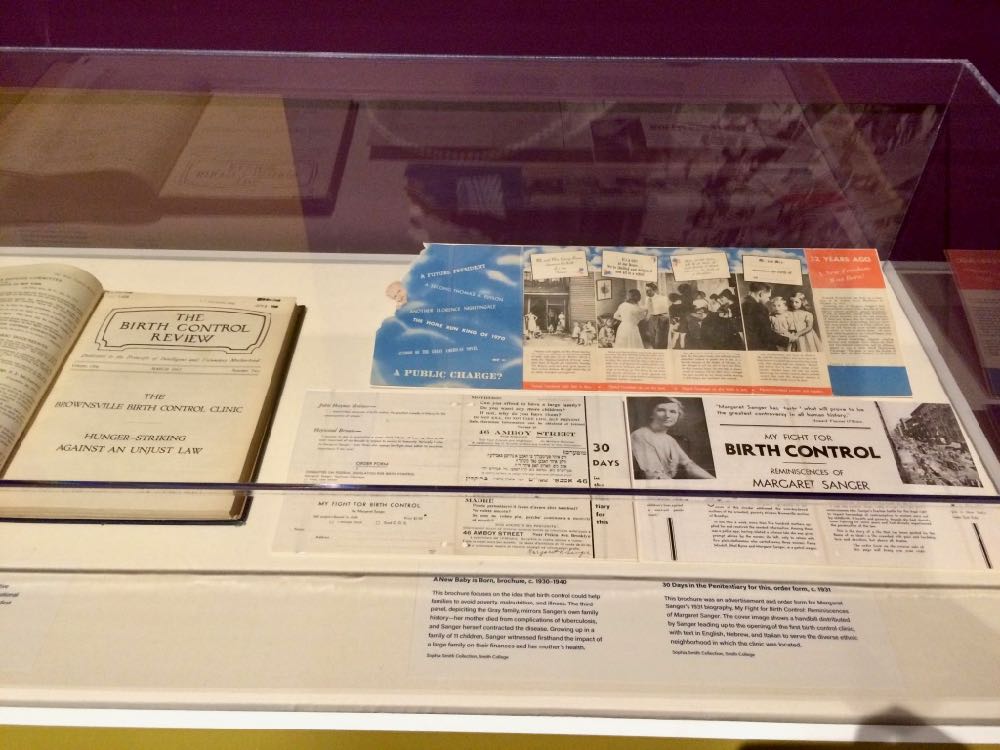

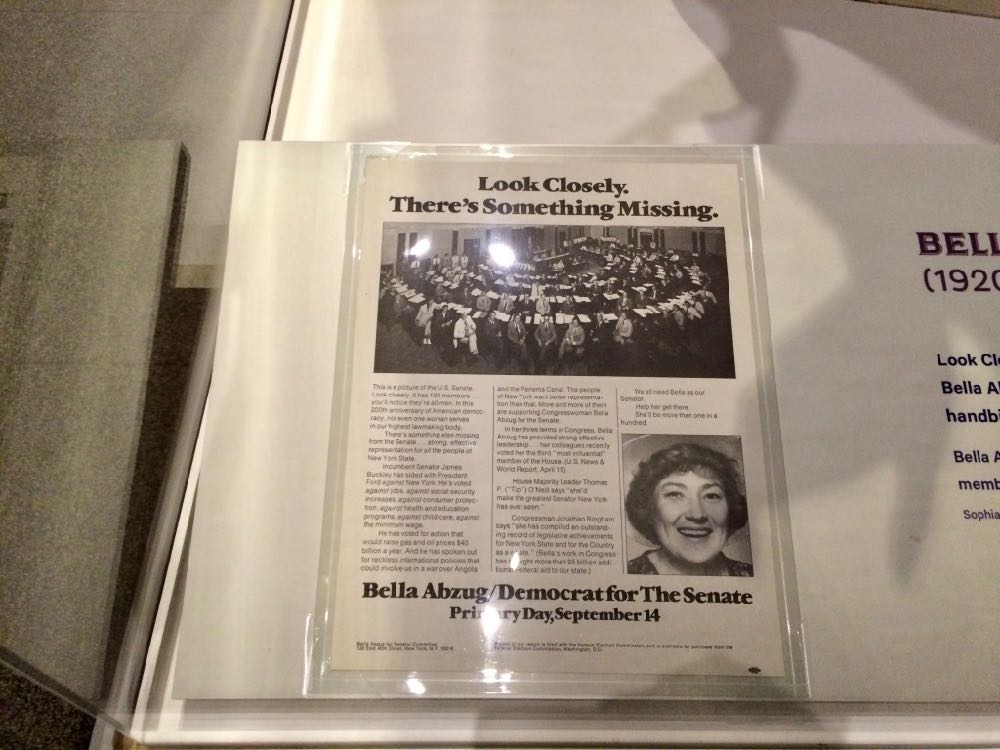

The State Museum has a new exhibit opening this weekend that highlights the history of this turning point. Four years in the making, Votes for Women: Celebrating New York's Suffrage Centennial includes more than 250 artifacts and images related to the suffrage movement -- from Elizabeth Cady Stanton's writing desk to campaign paraphernalia to Susan B. Anthony's alligator purse.

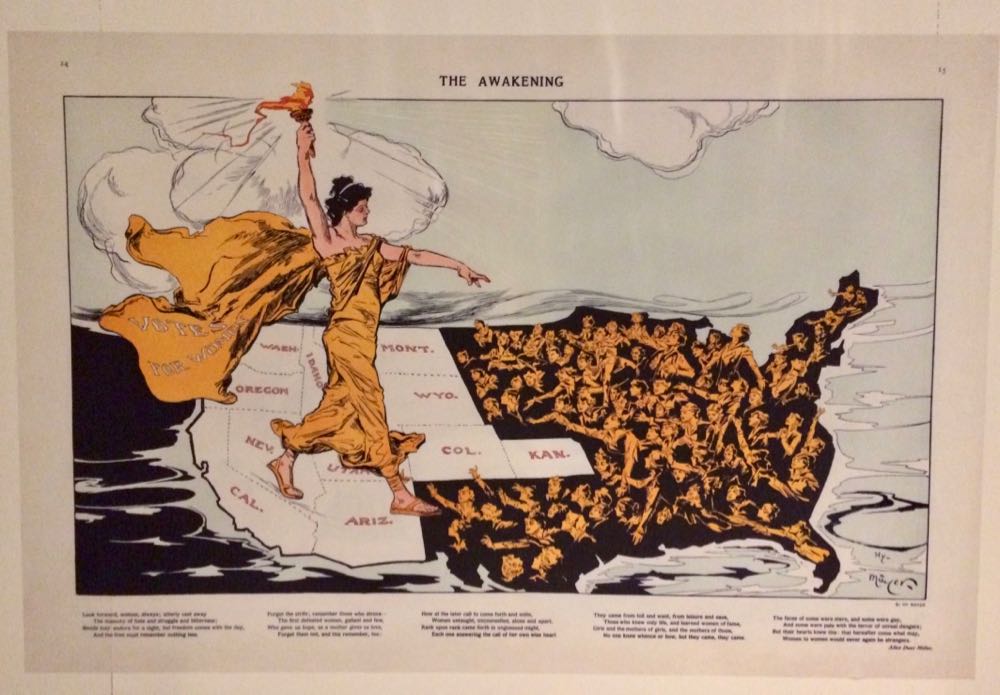

What's maybe more interesting about Votes for Women is how it places the push for suffrage in New York in the wider historical context of social and political movements, on a timeline that stretches many decades both backward and forward from 1917.

We got a chance to see the exhibit Wednesday during a preview, and talk with the co-curators about how New York experienced this movement...

Photos

There are a handful of pics from the exhibit at the top in large format -- click or scroll all the way up.

Talking with the curators

The curators behind Votes for Women are historians Jennifer Lemak and Ashley Benton-Hopkins.

A lot of people learn about women's suffrage in school and either because of the way it's presented or just because of the way that we end up learning history in classes, it maybe comes across almost as this discrete event. It's like it changed in a state, then there was an amendment and [then] it was all across the country. What's interesting about this exhibit is the way that it highlights how this movement was a long process that happened over many decades. So what are some other things you think that maybe we don't tend to understand about how all this came about?

Ashley Hopkins-Benton: I think to start with in addition to some school kids getting the idea of the 19th Amendment and that happening, the only other thing that maybe they learned about is Seneca Falls in 1848. But it's really a continuous story. And beginning with the time of the American Revolution women were already starting to think about, well, where are our rights? The men are fighting for their rights. But it should be our turn next. So they're discussing that very early and especially in New York State. They're really thinking about what laws should be changed and what rights that they should have.

Was there something about New York during this time that made it such a fertile ground for women to organize over this issue?

Ashley Hopkins-Benton There was a lot of other reform work going on at the time and there were discussions about women's rights within the abolition movement, within the temperance movement, at some of the utopian societies that were founded in New York State. So there were there were a lot of people here that were talking about those kinds of issues.

Jennifer Lemak: I was just going to say I think the short answer is the Erie Canal.

Really? Why is that?

Jennifer Lemak: The Erie Canal, it brought a hotbed of reform across the state. That's why that whole section's called the burned-over district. So it brought all these new people and new ideas into the state around the same time -- and not only reformers, but immigrants and just all sorts of new folks and new ideas. Yeah, so, I was going to say... it's always the Erie Canal.

I think what's also maybe surprising to a lot of people is that we look back now and, yes, obviously women should be able to vote. But there was also at the time a very prominent anti-suffrage movement. So how strong was the opposition to suffrage at this time?

Jennifer Lemak: It was strong enough for the vote to be voted down [in New York] in 1915. And there were pockets, depending on who lived where, Albany was anti-suffrage for the most part and it was mainly because of the women who lived here.

In 1917 Albany actually voted against suffrage, correct?

Jennifer Lemak: They did. I don't remember the statistics, but they certainly did. And so in 1917, overall upstate voted suffrage down, but there was enough people in New York City who voted for it that overall suffrage won.

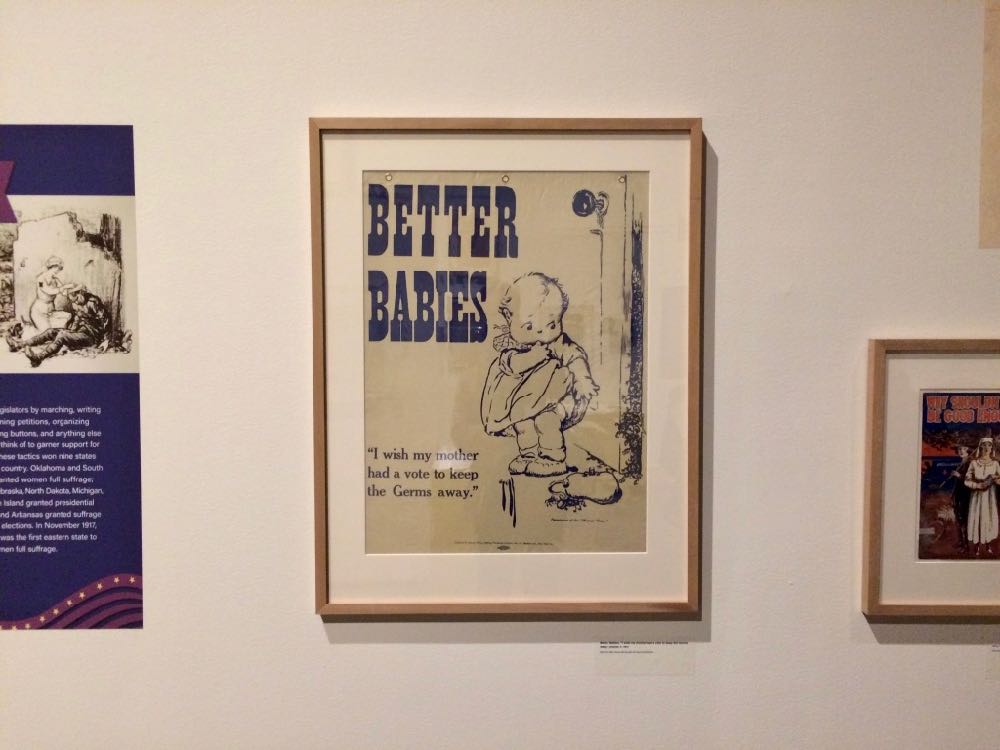

And suffrage really came out big in 1917 in the immigrant communities mostly because of the work of suffragists and visiting nurses. Because they would go into the homes and kind of educate the families on why women needed the vote and for the most part if you look at New York City per ward most of the immigrant wards came out in favor of suffrage -- over other communities that weren't so heavily immigrant.

So women win the right to vote here in New York State. They've been working for this for many, many years and then there's the 19th Amendment. Does this movement go away or what happens to it?

Jennifer Lemak: Well, that's what this purple section we're standing in is all about! I think that some women thought that we're going to get the vote, everything will be the same.

But in reality women ended up voting the way their husbands voted and the way their fathers voted. And it was really Alice Paul and kind of her more militant suffragists that said, OK we got the vote, but we're still not equal. How are we going to change that? And that's when the Equal Rights Amendment comes in in 1923. Alice Paul and some of her fellow suffragists who started the National Women's Party, which was the militant arm of the suffrage movement, they go to Seneca Falls in 1923 on the 75th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention and say we need an amendment that puts this into the Constitution that says that women are equal. And that amendment still hasn't passed.

What do you think are some lessons that we can take today from this whole episode in history?

Ashley Hopkins-Benton: I think just the way that these women organized, and the way that they collaborated and worked together and they thought really strategically about what groups to work with and how that could get their message across.

Jennifer Lemak: It's actually what I was going to say, too. One thing that you don't learn in school is that these women really understood how the process worked, how the legislature worked. They knew if they didn't have the vote, you know, what were my other options? It was a petition campaign. It was me speaking to a group of people.

I don't know if kids in school understand the political process today. It's not something that you just show up in November and do. But for the women of this movement they knew how it worked and they knew how to work within it without the vote. So I think that's why those ribbons for the 600,000 petition that they they were able to get in 1893, it was a big deal. I mean it couldn't just have social media all over the place. You had to get out there and get the petition. And then in the referendum section you really kind of get that understanding that they knew exactly what politicians to go to to get the rest of them. So they were very well educated on the ways of Albany.

Ashley Hopkins-Benton: And that actually ties into something that our education department is working on. They're doing a series of lesson plans that teachers can use in their classroom in conjunction either with a visit to exhibit if they're lucky or with the catalog that goes along with the exhibit. And one of the focuses has been talking to students who are not old enough to vote about how they can be involved in the political process and be involved in their communities in the same way that these women were using petitions and were using letters to the editor and were using speeches and using the same tools.

This interview has been lightly edited.

Exhibit info

Votes for Women: Celebrating New York's Suffrage Centennial open to the public November 4 and will be on display through May 13, 2018.

The exhibit will also be open Monday, November 6 -- when the museum is otherwise closed -- for the anniversary of the 1917 vote. Jennifer Lemak and Ashley Hopkins-Benton will be leading a short lunchtime tour of the exhibit that day. It's free.

... said KGB about Drawing: What's something that brought you joy this year?