The seed for so many backyard gardens

From an 1888 Shaker Seed Co. wholesale catalog from Mount Lebanon, New York. / via Archive.org (U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library)

Some ideas seem so obvious that the might has well have just sprouted from ground, everywhere, after a rain and people just happened upon them. But at the beginning they're not so obvious and someone has to be the first person to recognize the idea and grow it.

So it was with some delight that we recently learned more about how the Shaker communities in this region were probably the first people in the United States to start businesses selling seeds for backyard or "kitchen" gardens. And putting the seeds in the ubiquitous paper envelopes? Yep, Shakers. And store displays, kind of like the racks that stand in hardware stores and supermarkets today? Shakers did that, too.

Here are a handful of facts about the Shaker seed business and its roots here.

Origins

The exact beginning of Shakers selling seed for home gardens isn't clear -- but it was probably one or both of the Watervliet (now Colonie) and New Lebanon Shaker communities, as noted in Stephen J. Paterwic's Historical Dictionary of the Shakers. There's a record of Joseph Turner setting aside land at the Watervliet community in 1790 for the specific purpose of growing seed to sell. And if Watervliet was the first, New Lebanon hopped on the idea soon after.

Growth

The seed business was a good fit for Shakers, considering their emphasis on work and order and simple quality. And the idea spread to many other Shaker communities during the early 1800s. New Lebanon became one of the biggest producers of seeds. From a 1993 paper by Laura Paine in the HortTechnology:

Early offerings of seeds were limited, but, as sales increased, many varieties were added to the seed lists. New Lebanon records indicate that the best-selling seed in the late 1700s to early 1800s was onion. Seedsman Artemas Markham lists 201 lb of onion seed produced and sold in 1795. Other vegetable varieties sold in that first year included scarcity beet (a fodder beet, also known as mangel-wurzel), carrot, cucumber, and summer squash. In that year, a combined total of 44 lb of these varieties was sold, with an income listed at $406 (Andrews and Andrews, 1974). The next year, records indicate that two varieties of turnip and three of cabbage were added to this list. By 1800, income from sales of seeds other than onion at New Lebanon had more than doubled to $1000. A number of societies joined the early producers in the first years of the 19th century. By 1820, nearly all the Shaker societies were producing seed for sale.

Around this time the Shakers were pretty much the only source of commercial garden seeds for people in rural communities. As other producers got into the game, they sourced seeds from the Shakers. And the Shakers in turn got seeds from the outside world. But concerned about quality -- and perhaps sensing a branding opportunity -- the Shakers soon decided to only share seeds among themselves as a way of safeguarding their rep for high-quality and reliable product.

Competition

The Shaker seed operations would later face stiff competition from other companies, especially after the Civil War, but initially some of the toughest competition came from each other. And this part of the country was a hot market, with the Watervliet and New Lebanon communities at one point agreeing to use the Hudson River as a market dividing line so they wouldn't be at odds. But other communities got into the game, which led to some (polite) complaining and negotiating among the communities, as chronicled in Work and Worship Among the Shakers: Their Craftsmanship and Economic Order by Edward Deming Andrews and Faith Andrews.

Packaging

A Shaker seed display box from the New York State Museum collection.

The Shakers are credited with first using the now ubiquitous small paper packets to sell seeds to home gardeners. (James and Josiah Holmes of the Shaker community in Cumberland County, Maine are said to be the inventors.) And the packets were originally very plain, in part because that fit with Shaker beliefs and aesthetics. And they were printed by the Shakers themselves. But as competition increased, the Shakers adapted, creating more eye catching packaging. And they distributed them to stores in boxes that doubled as displays. From Inspired Innovations: A Celebration of Shaker Ingenuity by M. Stephen Miller:

In more rural areas, Shaker seed peddlers often left their filled boxes at general stores, where merchants would display them on counters with their lids open -- exposing a printed black-and-white seed inventory. After the Civil War, the inventories were brightly colored -- in the hope of attracting the interest of potential buyers. These lists used commercial color lithography and saturated colors that promised abundant yields of gorgeous vegetables for any buyer smart enough to purchase Shaker seeds. The merchant agreed to accept a fixed commission of 33 1/3 percent of each seed package sold. When Shaker brother retrieved the boxes at the end of summer, it was simple to calculate what had been sold and the commission due -- for the numbers of seed envelopes of each variety were either hand-written or printed on each interior seed list. Typically, each package -- no matter the variety -- sold for six cents.

There are a bunch of images of Shaker seed packages on Pinterest, ranging from the early plain versions to some of the gorgeous later versions and the display beautiful boxes that housed them.

Another retail innovation: a combination seed catalog/gardening manual, first issued by Charles Crossman at New Lebanon in 1836.

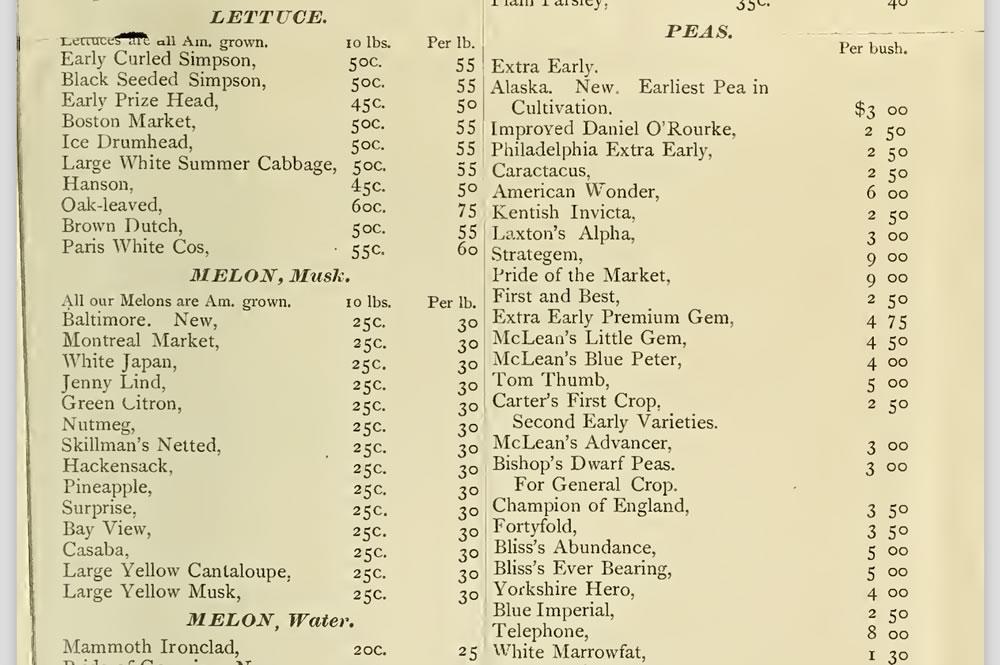

From that 1888 Shaker Seed Co. wholesale catalog from Mount Lebanon. / via Archive.org (U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library)

Vegetable varieties

There's a Mount Lebanon Shaker wholesale seed catalog from 1888 on Archive.org and it's kind of fascinating to see all the different varieties of vegetables that were available, with multiple types of beets and peas and celery (!) and cucumbers and so on.

If you're a gardener you'll also recognize at least a few varieties still grown today in backyards. Among them: Danvers carrots, Hubbard squash, French Breakfast radishes, and Black Seeded Simpson lettuce.

Other unfamiliar varieties have fantastic names, including: Turner's Incomparable Dwarf White celery, Strategem peas, and the Hathaway's Excelsior tomato.

Speaking of tomatoes... The Shaker catalogs chart the somewhat cautious embrace of the plants, which were new to Americans in the 19th century. From that paper by Laura Paine in the HortTechnology:

Introduced as an ornamental to Europeans from its native South America, the tomato was thought to be inedible during the 18th and early 19th centuries. First listed in Shaker seed catalogs in 1835, it was described as a "harmless, very delicious, wholesome and cheap vegetable." In 1843, catalogs were still cautiously referring to the tomato as "a healthy vegetable... though generally not very palatable at first.. .a great favorite once we become accustomed to it" (Sommer, 1972).

Things have changed a bit since then.

Shaker seed history talks

Two upcoming local events about this topic:

June 9: Garden Talks and Teas at The Ten Broeck Mansion

"Did you know the Albany Shakers were the first to develop and sell seeds in paper packets? Discover the fascinating history of the Shaker garden industry. After the presentation, enjoy light refreshments and explore the lush mansion gardens." 2 pm -- $20

June 23: Shaker Heritage Society Garden and Herb Tour

"Learn about the Shaker herb and seed industry, followed by a walk in our heritage herb garden, where you can see and smell over 100 herbs!" At the Shaker Heritage Society site in Colonie near the airport. 11 am -- $5

Earlier

Say Something!

We'd really like you to take part in the conversation here at All Over Albany. But we do have a few rules here. Don't worry, they're easy. The first: be kind. The second: treat everyone else with the same respect you'd like to see in return. Cool? Great, post away. Comments are moderated so it might take a little while for your comment to show up. Thanks for being patient.

... said KGB about Drawing: What's something that brought you joy this year?