The art and science of maple sugaring

You might have a picture in mind when you think about maple syrup: a bucket hanging from a tree, smoke from the chimney atop a sugar shack, sap boiling in a cauldron.

While there are places where that picture still fits, modern maple sugaring also involves a range of advances in technology: pipelines, vacuums, evaporators, reverse osmosis machines.

Making maple syrup is a combination of science and craft. And in talking with two local sugarmakers, I found that there are a number of surprising factors that influence both the process and product in making maple syrup. From climate change to soil composition to bacteria in the sap, these are the elements that lead to some of the purest sweet stuff out there, much of which is coming from our backyard in upstate New York.

On the eastern outskirts of Troy, Mark Cipperly, owner of Capital Agway, has been making his own maple syrup for 13 years and selling it in-store. Half his operation is on buckets, half on a pipeline, a network of tubing that collects sap from the trees and brings it to a central location.

"As far as the processing operation, it's on a modern evaporator," Cipperly says. The machine spreads the sap over a wide area, reducing the boiling time compared to an old-fashioned cauldron. "But it's still wood-fired, so a big part of the work is getting the wood, cutting the wood."

When the sap is running freely, it's a good but exhausting time for sugarmakers. For every 40 gallons of sap collected, 39 must be boiled off to produce just one gallon of maple syrup.

This year, the weather has been a friend to Cipperly and other sugarmakers. That's critical because, as Cipperly explains, weather conditions are the most important factor in how much syrup is produced in a year.

"To make sap run, you need to have a pressure differential within the tree and outside. The biggest way to get that to happen is with a temperature swing. If we get it below freezing at night, then well above freezing during the day, that's enough to make sap come forth."

But with current technology, that's not the only way to do it, says Dick Ogden of Running Brook Sugar Shack in Hoosick Falls, whose syrups can often be found at The Cheese Traveler in Albany. The vacuum system "tricks the trees," he says. "You're making them think the barometer has changed so the trees will run," which allows sugarmakers to get more sap from each tree and extend their season a bit longer than if fully beholden to Mother Nature.

An evaporator at Nightingale Maple Farm in Amsterdam in 2011. From a photo tour of how maple syrup is made, by Liz Clancy Lerner.

Being able to extend sugaring season by even a day or two is important in this age of climate change, which is all too apparent to sugarmakers whose business relies on traditionally long and cold winters -- one of the reasons why New York is second only to Vermont in maple syrup production nationwide.

"We would start boiling the first of March and go into April when I started," says Cipperly. "Now we have to be ready by Presidents' Day and we're cleaning up in April." Last year, during the oddly early and warm spring, he says their final boil was on March 15.

Terroir and bacteria

But once boiling begins, there are a number of factors that go into the final maple product that reaches the consumer. According to Rowan Jacobsen, author of American Terroir, some believe that maple syrup flavor can, like wine, be affected by environmental elements: elevation, climate, soil, genetics.

Ogden, who rents over 1300 trees near his home just west of the Vermont border, says he's blessed to be located in the heart of the Taconic Mountains for one major reason: the limestone in the ground leads to alkaline-heavy soil and trees whose sap is high in sugar content.

"The limestone makes everything sweet," says Ogden. "I almost dare say this area has got the sweetest syrup in the country."

Cipperly says that to him, the element that has the biggest effect on the end product is sap quality. "That relates back to how long it takes to turn the sap to syrup, and the biggest part of that is bacterial growth," Cipperly says. There's no bacteria in the final syrup product -- it's killed during the boiling -- but there's bacteria in the sap as it comes out of the tree. And "bacteria in sap feeds on sugar, so the more bacteria there is, the more it eats the sugar in the raw sap."

The bacteria plays a big role in the final product -- specifically the color and grade of the syrup. The microbes consume sucrose in the sap, breaking it down into simpler sugars. Amino acids in the sap -- along with heat -- then brown the syrup through the Maillard reaction. (You know this reaction even if you're not familiar with the name -- it's responsible for a wide range of tasty foods, including browned meat and toasted bread.)

A sample from the 2012 batch of Grade A dark amber syrup at Mountain Winds Farm in Berne.

So, the more bacteria and the longer they've had to work, the darker the syrup. Grade A light amber, known as "fancy" in Vermont, is the first produced in a season. Bacteria levels in the sap are relatively low early in the season, resulting in a light-colored, delicate syrup with a relatively mild flavor. For a long time that was the most sought-after syrup by consumers.

"Fifty years ago when there was no disconnect between the consumer and producer, the consumer knew it was more difficult to make light syrup," says Cipperly. That awareness led to demand.

But now, many maple syrup lovers are turning to the medium and dark ambers, which possess fuller, more robust flavors compared to the lighter syrup. These are the product of later-season sap, which has higher levels of bacteria -- and, a result, more simple sugars on which the Maillard reaction can work. Both Cipperly and Ogden say the darker, the better.

"I usually prefer a dark on my pancakes and French toast, and a medium on my ice cream and stuff like that," says Cipperly. And if he's out for breakfast somewhere that serves only corn syrup-based table syrup and he hasn't come packing his own maple? "I'm having eggs. I don't dabble in that other stuff anymore."

New York vs. Vermont

But even with such a good product being produced right here in upstate New York, it can be a challenge to not have the name "Vermont" on the label. Ogden sells his syrup at the Bennington Farmers Market and says he gets some grief on occasion from locals. "Some of the old timers will say, 'You've got a lot of nerve bringing that up here from New York!'"

"A big part of that is just marketing," says Cipperly. "They can document that there are some very subtle differences in Vermont maple syrup, and they've built a brand off of that."

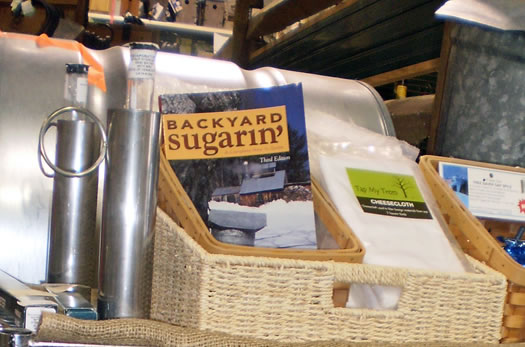

Backyard maple sugaring supplies at Capital Agway.

It's important to understand the level of pride and craftsmanship that goes into the maple syrup produced right here in New York, whether by some of the smaller producers, like Cipperly and Ogden, or the backyard enthusiasts, whose numbers are growing. Ogden sells the buckets and other materials needed for sugaring in his Capital Agway store.

"A lady came in the other day and bought two buckets and two taps," says Joe Vars, who works at the Agway store and has tried his own hand at small-scale sugaring in the past. "It's as much work as you want to make it. You can make it enjoyable doing two buckets, boil it down, get yourself a quart or two of syrup, do that on your kitchen stove."

Appreciation for maple syrup is on the rise. The pure stuff can be found more frequently now in area restaurants and supermarkets, not to mention specialty stores. Demand and prices are up, turning syrup into a hot commodity -- there was even a "massive maple syrup heist" in Canada recently. But Cipperly says syrup makers have maintained a friendly and open attitude.

"Sugarmakers in general have no secrets. They'll tell you anything, will open the door to their sugarhouse for anybody to have a look. This is unlike any other line of work I've been in. It's been a real breath of fresh air."

Jeff Janssens writes about food and beer at The Masticating Monkey.

Earlier on AOA:

+ Massive theft from Canadian strategic maple syrup reserve (not an Onion story)

+ A good by photo tour by Liz Clancy Lerner about how maple syrup is made

Hi there. Comments have been closed for this item. Still have something to say? Contact us.

Comments

Nice. I like to visit sugarhouses, so for what it is worth I made a Google map of the ones that were open to public the past two weekends. Have at it.

The people in this industry are really friendly, I wouldn't be surprised if they still showed you around even this weekend. I went west a few years ago to check The Adirondack Gold Maple Farm and Toad Hill Maple Farm near Thurman, and east a few weeks ago to check the goods near Greenwhich, NY. The Sugar Mill Farm LLC had the best pancakes, and the guys at Wild Hill Maple the sweetest welcome.

... said -S on Mar 25, 2013 at 5:27 PM | link

Great article! I didn't realize the reason for the different shades of color for real maple syrup or the environmental factors that play a crucial role in the end product. There is a nice yearly festival on Malabar Farm State Park near Mansfield, Ohio that displays a theatrical demonstration of how maple syrup was produced over camp fires and usually turned into maple sugar. They also have a modern process that can be toured and taste-testing available throughout. These are real production processes. http://findtimeforfun.com/maple-syrup-festival-malabar-farm-state-park/

... said Chad on Mar 29, 2013 at 7:48 PM | link