Agrippa Hull, Thaddeus Kosciusko, and how Thomas Jefferson didn't hold up his end of the agreement

Agrippa Hull and Thaddeus Kosciuszko

Somewhere between three and four hundred black men served in the Continental Army during the battle of Saratoga, one of the moments credited with the turning the tide during the American Revolution. It's difficult to tell exactly how many because soldiers were not identified by race on the roster. And like their numbers, many of the stories of the black soldiers of the revolution are missing from history.

One of the men at the battle we do know about is Agrippa Hull -- a free black man who served for nearly six years, most of them as a personal aid to Thaddeus Kosciusko, the mastermind behind the battle of Saratoga and the namesake of the twin bridges on the Northway.

Hull was the inspiration behind Kosciusko's effort to free hundreds of American slaves. An effort that ended up being thwarted by his friend -- founding father Thomas Jefferson.

Black soldiers in the Revolutionary War

The Saratoga National Historical Park in more recent times. / photo: Lauren Hittinger Hodgson

The attitude of the Colonial government toward African American soldiers was complicated. In December of 1775, George Washington defied a Congressional ruling stating that "negroes, boys unable to bear arms, [or] old men unfit to endure the fatigues of the campaign" were not to be enlisted in the Continental Army.

Washington had learned that there were black men who wanted to serve. In addition, the British were offering freedom to any slave who fought for the Loyalists. So Washington allowed free black men to enlist.

Congress soon approved the move, but controversy continued. Albany's own Philip Schuyler -- a major general in the Continental Army -- wrote to another general complaining of the troops he had been sent: "... of the few Continental Troops we have had... one-third part is composed of men too far advanced in years for field service, of boys, or rather, children, and mortifying barely to mention, of Negroes." Schuyler also complained about his troops at Ticonderoga to George Washington, writing "I wish one third of them had not been little Boys and Negroes."

Yep, that guy.

Yes, that's the guy whose statue stands in front of Albany City Hall today. But this isn't Philip Schuyler's story. It's Agrippa Hull's. So back to it.

Agrippa Hull

Massachusetts was one of the first fronts to integrate its militia. That's where Agrippa Hull -- a free black man from Stockbridge -- enlisted in 1777. Hull was about 18 years old at the time. He first served as an assistant to General John Patterson.

He soon transferred and played the same role for the Thaddeus Kosciusko, a military engineer from Poland who was the architect of the Continental Army's successful stand at the Battle of Saratoga.

Hull and Kosciusko

Eric Schnitzer, a historian at the Saratoga National Historic Park, says there is evidence that Agrippa Hull served at the Battle of Saratoga, but he didn't see combat there.

"Hull is listed as private soldier number 27," says Schnitzer, "and he signed up to serve for the duration of the war. At the time you could sign up for three years or the duration."

Schnitzer says Hull would have been at Saratoga for the surrender of British general John Burgoyne.

Gary Nash -- a historian and author who wrote a book about Agrippa Hull, Thaddeus Kosciusko, and Thomas Jefferson -- says Hull was what would have been referred to as a batman. He served at Kosciusko's side, sending messages, getting his uniforms ready, preparing his tent, whatever Kosciusko needed. But Nash says these two had a much deeper relationship.

Thaddeus Kosciusko. / via Wikipedia

"Because of his position as an aide," Nash points out, "Hull was always at the side of a senior officer, and he developed an emotional closeness that would never normally exist between enlisted men and officers."

Hull was known for his sense of humor, and Nash tells the story of a night when Hull dressed up as Kosciusko at West Point and threw a party for some of his black friends. When Kosciusko returned home unexpectedly in the middle of the party, Nash says the officer laughed and played along with the role reversal game.

According to Nash, Kosciusko's service with African American soldiers, particularly Hull, had a great impact on him.

"He really came to admire these young African Americans -- particularly Agrippa Hull -- and it got him wondering whether this new nation should include the abolition of slavery."

A promise from a founding father

Kosciusko and Thomas Jefferson were good friends. Inspired by Hull, Nash says, Kosciusko made Jefferson an executor of his will with a specific goal in mind. The will called for Jefferson to use Kosciusko's war earnings -- some $15,000 -- to free Jefferson's slaves at Monticello, and possibly to purchase freedom for other slaves.

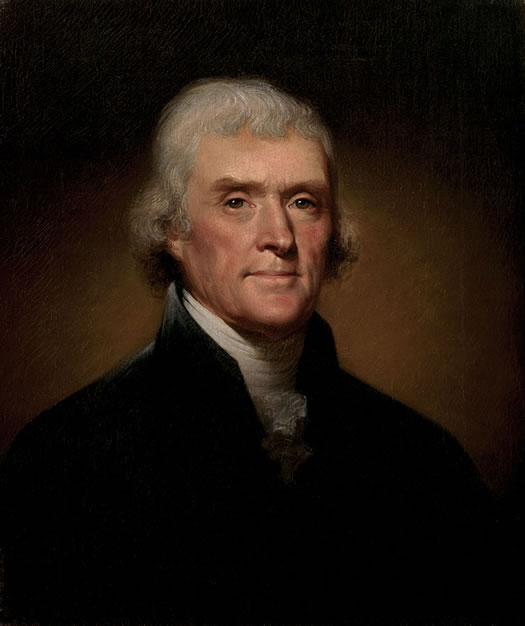

Thomas Jefferson's presidential portrait by Rembrandt Peale. / via Wikipedia

(Why didn't Jefferson simply free his own slaves without Kosciusko's money? Nash says it was partly because Jefferson was in deep debt. "He sold his precious library (to become the core of the Library of Congress), so that gives you an idea of how he dug a huge fiscal whole with his endless renovations at Monticello," says Nash. "When Jefferson died in 1826, everything had to be sold at auction to pay his debts -- the furniture, the paintings, the remaining books, the farm equipment -- and the slaves, several hundred of them.")

Kosciusko and Jefferson corresponded for the rest of Kosciusko's life -- he had returned to Europe after the American Revolution, later fighting for Poland's independence. But when Kosciusko died, Jefferson vacillated for a few years, and then refused to execute the will.

Nash said the price for a slave depended a lot on age, health, and other factors, but that on average, Jefferson could have purchased freedom for about $100-$150 per slave. Throughout his lifetime, Thomas Jefferson acquired about 600 slaves, so, in theory, there would have been money to free all of the slaves at Monticello -- if not others.

"And that," says Nash, "would certainly have made a huge difference -- the author of the Declaration of Independence, and third president of the United States freeing his slaves."

But none of that happened and eventually, Nash says, most of the money was returned to Kosciusko's family in Poland.

What happened to Hull?

After the war, Agrippa Hull returned to Massachusetts and made his home in Stockbridge, just over the border with New York. Over his lifetime, Hull worked for several people in town, including a Stockbridge lawyer.

George Washington had signed his discharge papers, something, Nash points out, that Hull was exceedingly proud of. Hull was owed a pension, but didn't want to turn over the papers with Washington's signature in order to collect it. One of his employers stepped in so he could collect what was owed to him without letting the document go.

According to Barbara Allen, the curator for the Stockbridge Library, Museum and Archives, Hull and his wife later went into business running parties.

"He's almost like a master of ceremonies or organizer of celebrations," she says. "His wife was a good baker so she ended up making some of the food for these parties and celebrations and things and Agrippa would be the one who would kind of organize it all and run it."

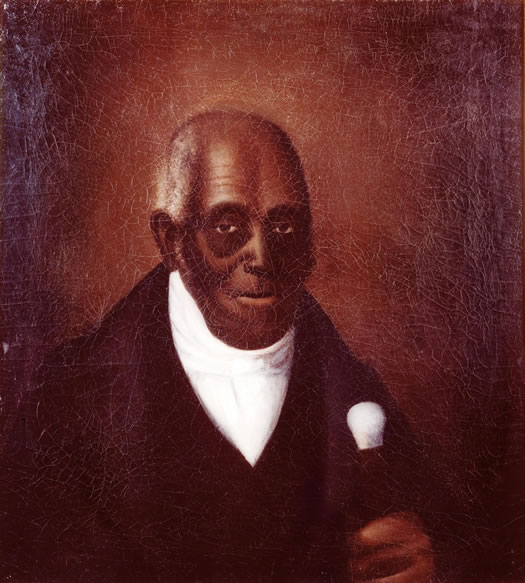

Agrippa Hull. / image: Stockbridge Library and Museum

Allen says Hull became a popular storyteller who would have subtle ways of taking anti-slavery positions. Among his common expressions: "You can't judge a book by the color of its cover. Many good books have dark covers."

Stories of Hull's pointed and deft humor include one about a visit he paid with an employer to see a "distinguished mulatto preacher," his employer asked him how he liked "nigger preaching." Hull replied, "Sir, he was half black and half white. I like my half, how did you like yours?"

Agrippa Hull lived until 1848, into the age of early photography. The Stockbridge Library and Museum had a daguerreotype of Hull. The photo was destroyed but an oil painting was made from it -- and it's on display in the library.

Barbara Allen and Gary Nash agree that until his death at age 89, Agrippa Hull was a well-known and loved figure in Stockbridge.

"We can talk about heroes large and small," says historian Gary Nash. "Jefferson and Kosciusko were known as big heroes, but for Agrippa to have such influence in Kosciusko's life, and the lives of others, he was clearly a hero. It's like that Margaret Meade line, 'Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.' Agrippa is one of them."

____

Earlier on AOA

Say Something!

We'd really like you to take part in the conversation here at All Over Albany. But we do have a few rules here. Don't worry, they're easy. The first: be kind. The second: treat everyone else with the same respect you'd like to see in return. Cool? Great, post away. Comments are moderated so it might take a little while for your comment to show up. Thanks for being patient.

Comments

Great article, 89 years old in the 1800s is a worthy story in itself! I admired his sense of humor. I will think of this story every time I cross the Mohawk on the Northway. Thanks AOA

... said Fox on Feb 24, 2016 at 3:50 PM | link

It seems to me the author missed the fact that Jefferson PAID FOR HIS TIME IN OFFICE and much of his debt came from inherited debt not of his own making, not Monticello. Jefferson was no saint but this piece of writing is very skewed. Tell the whole story not just the history that supports your view. Educate on all facts to bring up the intelligence of the world PLEASE!

... said Lauren on Feb 26, 2016 at 8:12 AM | link