Six huge institutions that set up here... almost

Not the Capital Region, obviously... but maybe it could have been. / photo: Flickr user Daniel Hartwig (CC BY 2.0 cropped)

It's Other Timelines week on AOA, in which we'll be looking at alternate histories of this place, about big and small things that did or did not happen.

Nationally-famous universities, a coordination point for the modern world, huge centers of industries, tech, and the economy -- they all happened here... almost.

For Other Timelines week, Carl Johnson shares a handful of huge institutions that almost ended up in the Capital Region...

The National University

It is odd, almost singular, that one of the most important cities in our nation's early history - a center of politics, commerce, and publishing - was never home to a major university. While Union College was certainly important, its range and size were always limited. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute was a premier center of specialized practical learning, but was also focused in ways that other colleges were not. And until 1962, what is now the University at Albany was simply a normal school - a teacher's college.

Well, it wasn't for lack of thinking about it. The idea of a National University went back to 1775, when Samuel Blodget suggested that the damage to colleges from quartering the revolutionary militia could be remedied by creating "a noble national university at which the youth of all the world may be proud to receive instructions."

The idea popped up over and over again, and in 1849 the idea was revived with a focus on doing it in Albany. The movement awakened so much interest among distinguished educators that conditional engagements are said to have been made with such men as Profs. Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Peirce, Arnold Guyot, James Hall, Ormsby M. Mitchell, and James Dwight Dana. No slouches.

The old Albany Law School building on State Street.

In 1851, this idea was incorporated at the University of Albany. A law school was organized first, followed by a department of scientific agriculture. A year later there was another attempt to grow this into a national university, but the somewhat odd result was the Dudley Observatory.

At the observatory's slightly wishful inauguration in 1856, many spoke of the need to establish a great national university, though by that time none of the speakers seemed to be suggesting that these three-ish institutions in Albany were it, and one went so far as to say that "in order to be national it should be located upon common ground. Under existing circumstances it would be wholly impracticable in New York, or Alabama, or anywhere outside the District of Columbia." He suggested the states have a role in both governing and paying for the institution.

Eventually, the Dudley Observatory, Albany Law School, and Albany Medical College (which predated the legislative call for such a school) would all become part of the loose federation known as Union University, created in 1873. The State Normal School became the NYS College for Teachers, which in 1962 finally fulfilled the promise of a university in Albany with the creation of the State University of New York at Albany.

And a true national university never happened, here or anywhere else.

Time itself

That whole thing where we refer to Greenwich time as the world standard for time? Well, here in the United States, there was a lot of energy behind the idea of setting Albany time as the national standard.

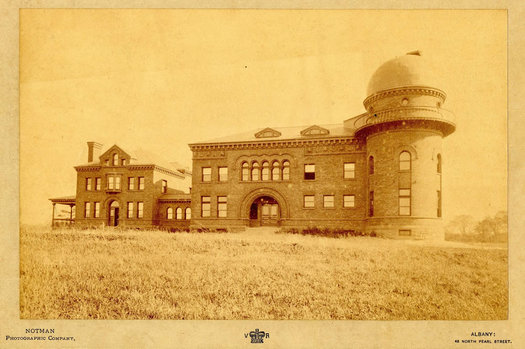

The old Dudley Observatory on South Lake.

The Dudley Observatory was brand new in 1856, a time when railroads still relied on highly inaccurate and inefficient local time, a perpetual frustration for anyone trying to build a railroad timetable that held any meaning. While the science-y types hold that noon has a certain astrological meaning, not every city calculated noon in the same way. As Harper's New Monthly Magazine noted in 1856, "An exact knowledge of time is also of vital importance to the conductors of all railroad trains. A small error in a conductor's watch has repeatedly been the occasion of the collision of railroad trains, and the consequent destruction of human life."

This had led, in Europe, to the establishment of Greenwich time, where the observatory at Greenwich would send out signals by means of dropping a ball from a mast and sending out an electrical signal to the local telegraph system. But while there was a form of standard time in Great Britain, US railroads still relied on highly inaccurate local time.

But the new Dudley Observatory was due to receive a highly fancy new clock, vital to astronomical measurements. They hit on the idea of using what was called the Corning Clock (for its major benefactor, the New York Central's Erastus Corning) to send telegraph signals to cities across the state, even across the country. Time balls (think of the Times Square New Year's Eve ball) would be set up to drop by telegraphic signal at a precise time, and all the local clocks could be set accordingly. The New York Central was willing to pay $1,500 a year for this service.

Such a nifty idea. And Albany was pretty excited at the idea of basically having time named after it. Unfortunately, that's not what happened.

The observatory's Dr. Gould was a lot of talk and little action, to the point that he was eventually shown the door (quite literally, under police escort). The clock was never actually finished. The cost of dedicated telegraph wires killed the time ball idea generally. And the railroads figured out how to standardize time on their own, by creating the time zones that plague us to this day.

The rival to the industry giant

An 1888 engraving of the Westinghouse Electric Company in Pittsburgh. / via Wikipedia

There's no question that Schenectady's industrial fortunes were long tied to two giants in two giant industries: American Locomotive Co. for railroad engines, and General Electric for the electric industry.

As those companies rose and fell, so did "the city that lights and hauls the world."

But there really should have been a third major player, every bit as giant in its time as those two: Westinghouse should have been in Schenectady.

George Westinghouse Sr. was a Vermonter who headed west to farm, and then came back east a bit, to Minaville in Montgomery County in New York State. He was a tinkerer, and while there started devising ways to improve threshing machines and other agricultural implements. He took up actual manufacturing in Central Bridge, and eventually came to Schenectady in 1856, at a time when broom-making was the only big industry in town. He set about making agricultural machinery, mill machinery, and small steam engines there. He held at least seven patents for "horsepowers, winnowers, thrashing machines, and a sawing machine." The works of G. Westinghouse & Co. "long stood at the gate of the great works of the General Electric Company." They were along the canal at the south end of Washington Avenue, then Rotterdam Street.

He had three sons, one of whom, George Jr., was also a devoted tinkerer. He was schooled in Schenectady and attended Union College very briefly. While serving in the Navy during the Civil War, he received his first patent, for improvements to a steam engine. Back home, it is said that he witnessed a collision on the Schenectady-Troy railroad line that led him to the idea of developing a compressed air braking system that would let an engineer brake all cars simultaneously -- previously, they had to be braked one at a time.

George Jr. went into partnership with others to build his railroad equipment, but had trouble both with local steel manufacturers and his partners. Despite the natural connection to Schenectady, he found backing from a steelmaker in Pittsburgh who was willing to manufacture one of his inventions at their own risk and hire him on to sell it. He hadn't even begun his electrical work at that time, but from that time forth Westinghouse would be centered on Pittsburgh, where the Westinghouse Electric Company was founded in 1886 -- one year before Thomas Edison brought his Edison Machine Works to Schenectady.

One of the buildings incorporated into the works had, for many years afterward, fading paint that proclaimed its former existence as "G. Westinghouse & Co."

Plastics

Lots of people remember the old billiard ball factory that used to stand on Delaware Avenue at Whitehall in Albany, and may even know of the marker claiming that plastics were invented there.

One of the very earliest forms of plastic, celluloid, was indeed invented by John Wesley Hyatt (at another location closer to downtown Albany), but it seems like it should have grown into a much bigger industry in Albany than it did.

Hyatt worked in printing, working with materials that, when mixed together, created celluloid. Whether he discovered this by accident, as the official story went at the time, or he was aware of research using these materials in England is impossible to say. But he was the first to begin practical production of celluloid.

He first ventured into manufacturing checkers and dominoes, using a wood pulp and shellac mixture, but by 1869 Hyatt was using celluloid to make billiard balls, for which a suitable substitute for ivory had been sought for some time. Buttons and dental plates soon followed.

Hyatt was engaged in several simultaneous business ventures and partnerships, all complicated and perhaps with varying success, when he rather suddenly departed for Newark, New Jersey in 1873. Whether it was because of his somewhat tangled partnerships in Albany (the businesses continued without him, with his other partners in charge), or some perceived advantage of Newark, we simply don't know. But it was in Newark that he built up the Hyatt Celluloid Company, in partnership with his brother, and it was there they contributed to the nascent plastics industry.

Anyone who has had the pleasure of driving through the chemical processing corridor in New Jersey may view Hyatt's decision to decamp from the Hudson as a positive thing.

The financial industry

Today, American Express and Wells Fargo are two of the giants of the financial world. Interestingly, they both started in the same business: express package shipping. They were also both started by some of the same people. And they both had Albany roots.

A former conductor on the Boston and Worcester Railroad, William Harnden began an express parcel service between New York and Boston in 1839. Looking to expand, he hired Henry Wells to serve as his Albany agent in 1841. Wells thought that providing express service to Buffalo was the future, but couldn't convince Harnden, so he jumped ship and helped create the Albany and Buffalo Express, located in the Exchange Building. Eventually a connection was made with the Fargo brothers of Buffalo.

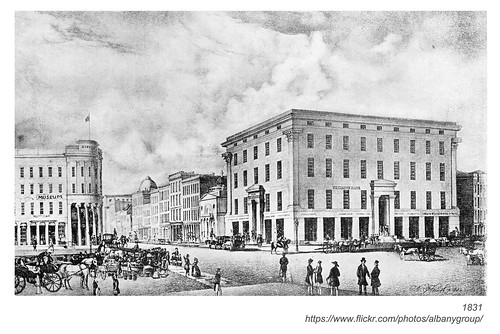

The Exchange Building (right) was once at State and Broadway.

In 1850, three express companies came together and formed The American Express Company. Henry Wells was president (until 1868), and William C. Fargo secretary. Of course, the company saw phenomenal growth, and very quickly established its headquarters in New York City, not Albany.

Over the years, it absorbed a number of rival companies, such as the United States Express Company and Pomeroy's Merchants Union Express Company. Many of these had their offices in the Exchange Building, at the northeast corner of State and Broadway now occupied by the former federal government building.

Shortly after the American Express was formed, Wells again wanted to push things westward, serving California. The other directors objected, so Wells and Fargo left the company and founded a new one with their names on it, rather famous for its California connection but which in fact had its origins right here.

Wells married a woman from Schuylerville, but never spent much time in Albany. Shortly after the American Express was formed, he moved to Aurora, New York. After he retired, he turned his estate into Wells College. Both companies he founded grew enormously, but they didn't do it in Albany.

That other university we could have had

Granted, this story may well be apocryphal, but let's believe it anyway: Stanford University could have been in Albany, but for a dispute over a burial plot.

Leland Stanford, who rose to be president of the Central Pacific railroad and along the way became fabulously well-to-do, was born the son of a tavern keeper in Colonie (then called Watervliet), apprenticed to the law in Albany, and eventually married Jane Lathrop, of a prominent local family.

While Stanford's fortunes were made in the west, family ties remained here. His brother owned the Stanford Mansion that was unceremoniously moved from its ancient setting in Niskayuna and now survives as a bank branch. Jane established the Lathrop Memorial Home for Children in Albany, close to the Fort Orange Club, part orphanage and part day care for working mothers.

The Stanfords had only one child, Leland Jr., who died suddenly of typhoid while vacationing in Europe in 1884. His final resting place was to be in Albany, where the families were from. It was reported by the Troy Press in 1891 that at the same time, Leland Stanford "had in mind a disposition of his millions that should forever celebrate the name of his son and that should be useful to the public." That would take the shape of a university, and the Press reported that Stanford had looked for a site that would have included his birthplace, west of Albany. However, in negotiating for a mausoleum with the Albany Rural Cemetery, the newspaper reported that the cemetery board wanted rather more than such a site would cost "a person of ordinary means," and Stanford decided to bury his son instead out west in Palo Alto -- and establish his university with a $20 million initial endowment.

Now, some have questioned this account. Only the Troy Press seems to have reported it, several years after the fact, and we haven't found any contemporary accounts that support that Stanford was on a scouting expedition. This could even just be a dig at Albany, one of many that came at a time when the two river cities were still arguing about the impact of bridges on their economies (short version: Troy hated bridges in Albany).

Still, we like to think it could have been true, and that a great university, something that was conspicuously lacking in a city of Albany's 19th century importance, could well have been here.

Carl Johnson blogs about local history at Hoxsie.

More from Other Timelines week

+ What would Albany be like today if the Empire State Plaza had not been built?

+ Other Timelines drawing: What's a local "what if" question that you'd love to know the answer to?

Hi there. Comments have been closed for this item. Still have something to say? Contact us.

Comments

Let's also remember how Intel wanted to build a chip factory here. The company was eyeing a site in Rensselaer county, just across the river from Albany. The projects was rejected by local residents who had concerns over toxic chemical discharge. Little did they understand that semiconductor industry has TONS of money to clean up their waste. I heard that a saw mill was approved instead. A saw mill, that discharges much higher levels of arsenic from pressure treated wood. Sawmills are exempt from some environmental regulations because they are so poor.

Chip fabs essentially print money but no, let's have a sawmill instead. Let's sponsor tuition for local students who will move to Oregon (best case) or get a part time job at Starbucks and qualify for food stamps. Let's pay insane school taxes to invest in kids who will move and eventually pay income taxes elsewhere.

... said Lu on Aug 1, 2017 at 6:52 PM | link