Growing a wider variety of flavors for cider

These trees will grow apples with a different accent.

On a small plot off to the side of an orchard in Kinderhook, there are rows of apple trees with names that are probably unfamiliar to even the most ardent apple lovers in America: Yarlington Mill, Kingston Black, Dabinett, Tremlett's Bitter.

That's understandable: These apples are not from around here. They're varieties that originated in England. And they have the sort of dry, astringent accent that registers right away. So bracing is the flavor of these apples that you wouldn't want to eat them.

And that's OK -- because they're meant for drinking.

A brief history of apples in America

Apples show up in North America in the early 17th century in New England. The first American variety was cultivated by an Anglican priest in what's now Rhode Island. From there apples spread to other parts of America and there's an explosion of different varieties. By the 19th century there's an estimated 14,000 varieties grown on this continent, with all different sorts of characteristics.

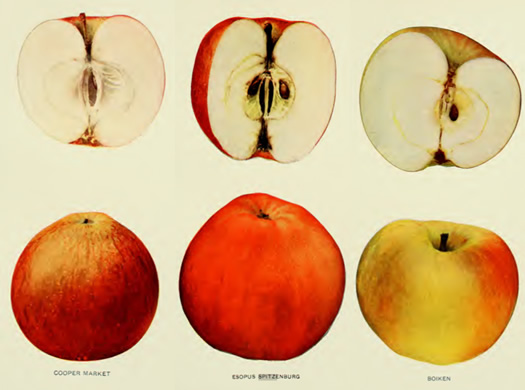

A few illustrations from The Apples of New York State, a 1903 New York Department of Agriculture publication that's one of the bibles of old American apple varieties.

Some of those apples were for eating fresh, or storing, or baking. But one of the most common uses for apples back then was making hard cider. In fact, Johnny Appleseed's efforts to spread the growth of apple trees was largely about cider production. These cider apples tended to be sour and bitter -- some people refer to them as "spitters" because of the reaction you'd have if you took a bite -- and it was those qualities that contributed interesting flavors to cider after fermentation.

Then Prohibition comes along, essentially killing off the hard cider industry in this country. Orchards are stuck with trees producing fruit that no one wants to eat, so the trees get ripped out or forgotten. Cider apple varieties in this country fade out.

Back to the present

Fast forward to the present: The hard cider industry in the United States -- especially in places like New York State -- is re-emerging, with a focus on making more sophisticated, nuanced ciders. And cider makers have been working with what they've got, which is mainly the 80-90 (or so) varieties of fresh eating ("dessert") apples that are grown in this country. But this is like painting with just a handful of basic colors. So cider makers are looking to expand the palette with old-school cider varieties.

"I mean, we have obviously figured out a way to make great tasting cider without them," said Alejandro del Peral, the founder of Nine Pin Cider in Albany, the first cidery to be licensed under the state's farm cidery law, which requires the use of New York apples. "But what this does is it opens up an entire new sort of flavor and quality that we can create different styles of cider."

One of those styles of cider is a type that's typically found in Europe, especially England and France. It has an astringency not that's unusual for American ciders. "It's sort of a mouth drying, warming, fuzzy kind of feel when you drink the cider," as del Peral describes it.

To get that effect, you need the right types of apples. Specifically, it requires apples that are high in bitter compounds called tannins. (Tannins show up in all different sorts of foods.) And without these cider apples, you can't make that sort of cider.

Bittersweet and bittersharp

Jake Samascott and Alejandro del Peral in the cider orchard.

"I think Alejandro has asked us that since day one," said Jake Samascott of Samascott Orchards in Kinderhook with a laugh. "What's it going to take to get you to plant cider apples?"

As it happened, it didn't take too much convincing.

Last year Samascott, which has an equity stake in Nine Pin, planted the first rows of its new three-acre cider plot alongside an edge of the orchard. It's there that the Yarlington Mill, Kingston Black, Dabinett, and Tremlett's Bitter seedlings stand along other bittersweet and bittersharp varieties such as Porter's Perfection, Redfield, and Franklin, as well as old dual-purpose varieties such as Belle de Boskoop and Saint Edmund's Pippin.

These sorts of trees tend to be different from the varieties typically grown here in the United States. One difference, for example, is that many of them produce apples very late in the season.

"I think there's going to definitely have to be a learning curve on varieties that do well in the Northeast," Jake Samascott said after a tour of the plot. "I think it's going to take a few years to really figure out what varieties are going to do the best here and what root stocks are going to do the best with the varieties. Every variety's different. So it's going to take some time to figure out what the best planting system is."

Toward that end, Samascott and a group of apple growers and cider makers from New York went on a tour of cider orchards in England this past June that was organized by Glynwood, an org focused on creating sustainable agriculture businesses in the Hudson Valley. Glynwood has also helped distribute some of these old varieties of cider apple trees to farms around the state, with the idea that growers will be able to share what works (and doesn't).

Samascott said that planting apples that can only be used for cider is a bit of a risk -- if they were dual-purpose apples, then they could just be sold for eating fresh if cider demand isn't there. But the recent strength in the state's cider industry gives them confidence to take the leap.

Also: "It's fun to put in the new varieties and see how they do. And. I'm excited to see what cider comes out."

Apples with a decidedly different heritage

OK, so those English cider varieties are like apple royalty, with old and distinguished family trees. But Samascott is also making room for some newcomers.

Alongside the rows of revered cider apple varieties in that three-acre plot, Samascott has also planted seedlings grown from actual seeds. Pretty much no one does this (on purpose, at least) because each apple seed is more or less a new type of apple -- and the chances of getting something good are very low. (That's why apple tree varieties are reproduced via grafting.)

Could be great. Could be a dud.

But they're giving it a shot, anyway. They pulled 25 seeds from than 20 different varieties of fresh eating apples -- varieties such as Jonathan, Northern Spy, and Golden Russet -- to see what happens. The odds are long. A lot of the seedings might not even produce fruit.

"I'm really excited," said Jake Samascott, pointing to the history of many famous apple varieties that were the result of random chance rather than focused breeding efforts. "I hope we get one great apple out of it, whether it's a great cider apple or a great dessert fruit. At the very least we'll have a lot of new varieties."

One of the apple trees along the perimeter of the pasture.

And even farther afield -- literally -- this fall Samascott and Nine Pin will be harvesting apples from old trees that are growing along the perimeter of the farm's cow pasture. These are trees that just sort of happened. They're the result of apples that were eaten by cows and the seeds were... well, you know. A few seedlings at the back edge of the pasture survived to maturity, and in contrast to typical orchard trees, they're now tall and bushy.

Some of these wild apple trees produce surprisingly large crops of apples. None of them are particularly good for eating fresh. But Alejandro del Peral said their bitterness could make for some interesting cider notes. So they're going to try making a few test batches with the wild crop.

Drinking the new old cider

Samascott will harvest the first crop -- a very small crop -- from the cider orchard this fall. Then Nine Pin will gauge the apples' sugars, tannins, and other qualities with an eye toward making cider.

Alejandro del Peral said if all goes well, those first batches of cider made from the new orchard plot could be available in Nine Pin's tasting room in 2018.

Earlier

____

Nine Pin advertises on AOA.

Hi there. Comments have been closed for this item. Still have something to say? Contact us.

Comments

This. Is. Fantastic.

... said Daniel B. on Oct 12, 2017 at 11:50 PM | link