787 is sticking around for a long time, but if you want to change it the time to start is now

Let's just get right to the point most people want to hear about: The new draft of the I-787/Hudson Waterfront Corridor Study doesn't lay out a detailed plan for making the sort of radical changes to the highway that so many people have desired for so long.

But the long-awaited report -- the product of a process that stretches back to 2014 -- does provide an extended outline of possibilities for potentially making over one of the Capital Region's key pieces of infrastructure and the Hudson River waterfront.

"We have options, what we need is a champion, we need support, we need funding to go to the next step," said Capital District Transportation Committee executive director Mike Franchini this week at an open house for the project at the Albany Public Library. CDTC headed up the report in collaboration with the state Department of Transportation, the city of Albany, and a team of consultants. "And that's really going to depend on the public and the municipalities in the area whether they want to go there or not."

Here's a big overview of what's in the report, along with a few thoughts for the future...

The draft report

The whole draft report -- all 162 pages of it (plus appendices) -- is online if you'd like to read through it.

There's a public comment period open until April 13 at 5 pm. (See the link for details about submitting comments online or via the mail.)

Some basics about the current situation (which is complicated)

This corridor study looked at the strip along I-787 from the Port of Albany north to the interchange with Route 7, and from the Hudson River on the east to Route 32 (Broadway) on the west. That's a stretch of roughly 9.4 miles of highway. And that corridor...

+ Crosses the city of Albany, the town of Colonie, the village of Menands, the city of Watervliet, and the town/village of Green Island.

+ Carries as many as 88,000 vehicles per day in some spots. The segment from the Dunn Memorial Bridge to Route 7 is the third-busiest interstate segment in the entire Capital Region.

+ Includes 56 bridges, of various designs and states of repair.

+ Has a key freight rail line that runs through the middle of it in downtown Albany, with a perpetual easement for the rail to operate within the right of way. The rail line averages eight rains per day.

+ A large portion of the corridor is in the 100-year flood plain.

In other words, this corridor gets a ton of use and it represents multiple layers of infrastructure.

This sort of infrastructure is expensive

And that infrastructure costs a sobering amount of money to keep going.

+ The corridor report estimates that just the cost of maintaining the current 787 infrastructure over the next 20 years is estimated to be $330 million (in 2015 dollars).

+ Roads, bridges, and related pieces eventually need to be rebuilt completely. And the report figures that the cost of the total replacement of the 787 infrastructure is estimated to be $890 million (in 2015 dollars). That's not for creating something new -- that's just basically buying a new version of what's already there.

The spending on the upkeep of something like 787 occurs in cycles, and as it happens we've just been through one of the waves of work. The state recently put $120 million into bridge and pavement preservation, much of it from Exit 23 to the South Mall Expressway/Dunn Memorial Bridge interchange. (The state has also put $22 million into rehabbing the South Mall Expressway.)

"We probably should have been doing this study 10 years ago. If we had done it earlier we might have gotten in before the DOT spent a lot of money -- and they had to, it wasn't safe in some cases," said Mike Franchini.

787 isn't going to change much for a long time

Given the recent cycle of maintenance spending, the corridor report notes that it's practical, from an economic perspective, to figure the projected service life of 787 in its current form will extend beyond 2035.

Yep, that means any big makeover of 787 wouldn't even start to happen for another 20 years.

Because of the way this sort of spending cycles, Franchini said it's important to get ahead of the next wave. "That gives us some time to plan, to do the feasibility studies, so at the next juncture -- before reconstruction, say -- we may have a plan to advance it."

The rail line problem

We're going to get some of the big potential changes to 787 in a second, but before we do it's important to highlight one of the reasons that making any large format change will be difficult: the rail line.

Before there was 787 on the riverfront in Albany, there were rail lines. And the fact that the current rail line -- which is a key connector for the Port of Albany -- literally runs through the middle of 787 in downtown Albany is a huge complication because any large change to the corridor there will have to solve the problem of what to do with the train tracks.

The report walks through some of the options for working around the rail line and none of them are great:

+ Raise the rail line: If that happens, it will be complicated to connect this elevated rail line to the other nearby parts of the rail system. Also: Now you have an elevated rail line on the riverfront, which is probably not what most people had in mind for the view.

+ Lower the rail line: "Drainage/dewatering, flood protection, retaining walls, and tunneling considerations for a depressed rail line would be a significant cost consideration for this option because the rail line elevation would be lower than the sea level elevation of the Hudson River."

+ At-grade rail crossings: In this scenario, the rail line would cross multiple streets at street level. These sorts of crossings tend to be dangerous and the federal government -- which oversees railroads -- discourages them.

+ Relocate the railroad: If someone could wave a magic wand, this would probably be the best option. But the big question is where? And is it possible to get multiple rail companies -- in this case Canadian Pacific and CSX -- to work together and share facilities?

So figuring out some way to work with/around the rail line will be a key part of any plan to change 787 in downtown Albany.

What the report says could be possible

OK, this is the part you've probably been waiting for. The report walks through a handful of potential large-scale strategies for 787 in the future. (The section starts at pdf p. 75 in the report.) And here are three that would mean big changes:

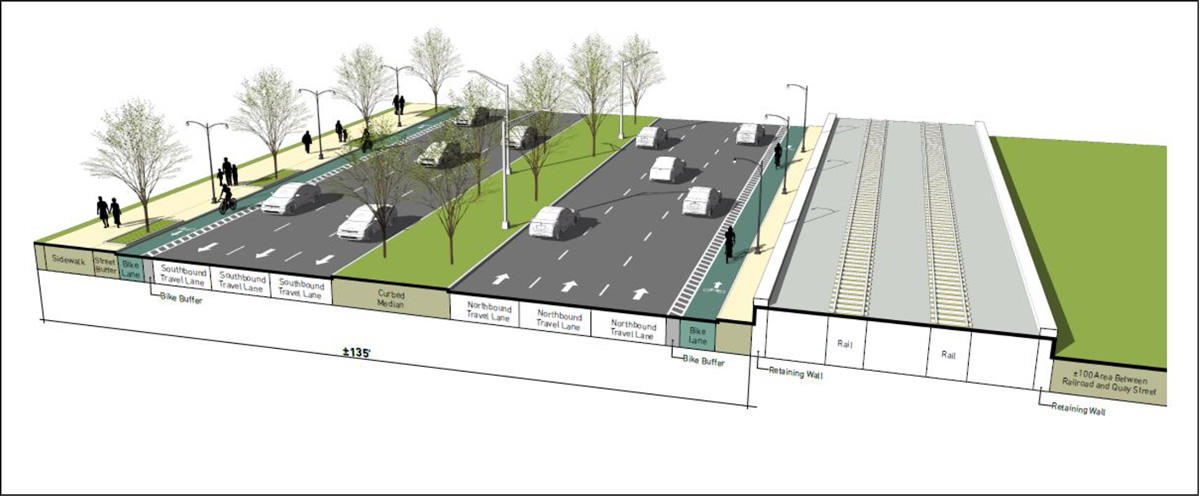

A cross section from the report of a possible boulevard-style format for 787 in downtown Albany. (Click for a larger version.)

Convert the segment of 787 right in front of downtown Albany into something more like a boulevard

This idea often comes up when people talk about wanting to change 787. The report provides a rough outline of a version of this idea in which the segment of 787 from south of I-90 would be turned into a non-interstate roadway at ground level. And it even provides a basic rendering of this idea with a configuration in which both sides of the roadway are moved to the west side (that is, the downtown side) of the rail line, leaving the former roadway to the east (that is, the river side) open for other uses.

The report notes that the high traffic volumes on this segment would be a challenge to handle on this sort of roadway, and it would still require a way of getting local traffic and people and bikes across the rail line.

Even so, from the report: "This would be a transformative project, which has the potential for significant positive impacts on the vitality of the City and downtown center. This type of project is consistent with similar successful projects in cities around the U.S. where transportation infrastructure has been modified to mend the negative effects of the Interstate System highway building era and re-energize their cities and waterfronts."

Lower the South Mall Expressway

Most of the South Mall Expressway (SMX) -- the elevated highway connecting the Empire State Plaza and the 787 interchange at the Dunn Memorial Bridge -- wasn't part of the narrow study area, but the report takes it up because it's so tightly integrated with 787. And the report provides a short outline for a plan in which the South Mall Expressway would be brought down to ground level and integrated with the existing street grid of the city.

This would be a hard project not so much because of the SMX itself, but because of the way it's tied into 787 and the Dunn Memorial Bridge at the massive elevated interchange and the differences in elevation. (Mismatches in elevation are a recurring issue with many potential changes to 787.) And as the report notes, it would probably have to be done in the context of reformatting the interchange and/or changing the Dunn. (Pull on one string and the whole tangled ball comes with it.)

But here's the thing: As much as everyone pays attention to the effect of 787 along the riverfront, there's an argument to be made that the South Mall Expressway is more damaging to the city of Albany because of the way it's cut the South End off from downtown, disrupted the street grid, and generally plowed a large swath of land through the city. So thinking about how to change it is worth the effort.

Shrink the interchanges

One of the recurring themes in the report is that much of infrastructure related to 787 is designed to handle much larger capacities than the use it actually gets. And one of the ways the report responds to that fact is by floating the idea of shrinking many of the interchanges along 787 (pdf p. 78).

Sure, there's the massive spaghetti bowl of an interchange at 787/South Mall Expressway/Dunn Memorial Bridge. But there's also the Clinton Ave interchange in the city of Albany, and the interchanges in Menands. These all suck up huge amounts of land -- look at them in satellite view sometime -- that could be used for parks or development or something other than underused ramps.

What the report says probably isn't a good idea

The report runs through a handful of ideas that came up for consideration, but were set aside. Among them:

Rerouting 787

The Watervliet Comprehensive Plan mentions rerouting 787 away from the waterfront so it can be opened up. But: "Substantial traffic diversions coupled with cost and the environmental challenges to implement outweigh the ability to have direct access to public space and economic development opportunities along the waterfront to pursue this strategy as part of the study."

Removing 787

Why not just rip the whole thing out? "While the strategy will connect communities to the waterfront and improve ped/bike mobility, there are major cost and feasibility implications that make this strategy unfeasible to pursue such as the rail infrastructure in the City of Albany, and connectivity to the [Dunn Memorial Bridge] and other adjacent river crossings that will continue to be factors affecting waterfront connectivity."

Sink 787

If 787 can't be moved, why not sink the whole thing below ground -- with or without some sort of cover -- to reduce its role as a visual and physical barrier? The report's answer, boiled way down and paraphrased in our words, not those of the report: that would be a crazy expensive engineering nightmare vulnerable to flooding and still doesn't solve the train track problem.

A rendering of what the Albany Skyway could maybe look like.

Smaller steps before big steps

So if the timeline for any major change is at least 20 years, what about the near future? The report basically tackles this question by recommending many of the strategies already in progress, mainly for communities to do their best to work with and around 787 where possible.

Among the examples:

+ The Albany Skyway project that plans to convert an underused 787 off-ramp at Clinton Ave.

+ The South End Bikeway Link that plans to connect the Helderberg-Hudson Rail Trail and the Mohawk Hudson Bike Hike Trail along a path partially constructed under 787.

+ The Menands Bike/Ped Connector that aims to convert a vehicle lane on the south side of the I-787 Interchange 6 on-ramp bridge into a multi-use path.

Changing the way we get around

A CDTA hype video for the proposed river corridor BusPlus "blue line."

One of the central issues in trying to change 787 is that, in general, the corridor gets a ton of use from people driving vehicles. And any potential change will have to figure out a way to manage all that traffic because in some cases it's too much for a boulevard-like road.

But you can also take this situation, flip it around, and look at it from the other end. Are there ways to get fewer people to drive cars? Are there ways to change the patterns about where people live and work? Are there better ways to get people from one place to other?

Because if there are good answers to some of those questions, then maybe fewer vehicles use 787 and the challenge of reconfiguring 787 gets easier. (The report takes up this topic under the banner of a planning concept called "travel demand management" -- see pdf p. 52.)

So, if you want 787 taken down...

+ It's also worth thinking about supporting more robust forms of public transportation like the bus rapid transit expansion that CDTA has proposed.

+ It's worth thinking about how you get to work. Do you really need to drive a car, by yourself, into work in downtown Albany?

+ And the next time you move, it's worth thinking about choosing a place that gives you transportation options beyond a car.

All these individual choices add up, and they can have a profound effect on the shape of the place we live.

This is ultimately about politics

Any large change to 787 will involve enormous amounts of planning and engineering. But it's not going to happen without politics first.

That's politics in maybe its most basic sense: A group of people getting together, forming a consensus about what they want to do, and then doing the work necessary -- over many years -- to focus attention and get the public and leaders on board so that there's action.

What's that mean in this case? Maybe it's a bunch of people creating a formal organization to find the money necessary -- probably $500k -- to do a detailed feasibility study about taking down the section of 787 along the downtown Albany riverfront. Then it's getting that feasibility study in front of all sorts of officials on the local, state, and federal levels. It'll be writing letters, making phone calls, rallying at the Capitol, holding events. It's getting candidates for elected officials to make the project an explicit plank of of their platforms. It will require sustained pressure over many years, arguing the case that this really is a good way to spend a billion (or more) dollars of public money.

And, yeah, that's daunting. It is, in some sense, a generational trip -- some of the people who set out to make this change might never see the destination. But the city will never get there unless people decide to start.

Earlier

+ What if tearing down I-787 could actually improve traffic?

+ Four takeaways from the kickoff for the study about the future of I-787 (2015)

Say Something!

We'd really like you to take part in the conversation here at All Over Albany. But we do have a few rules here. Don't worry, they're easy. The first: be kind. The second: treat everyone else with the same respect you'd like to see in return. Cool? Great, post away. Comments are moderated so it might take a little while for your comment to show up. Thanks for being patient.

Comments

I'm a car driver, but I have explored the bus system in the past for work. I'd love some type of light rail system but it may not be realistic. I support the rapid transit bus lines, but the pricing and efficiency and other things can be improved...

1. It's two bus routes (so one "transfer", which don't exist anymore) for me to get to work. I can walk to the second route, which takes me about half an hour. It'd be real nice if the system only charged me once.

2. the navigator card scanners are finnicky and slow. the card basically has to be placed on the scanner and not moved. Annoyed this passed their QA/UX design stage.

3. yeah, i'm gonna complain about winter and the unshoveled sidewalks and inaccessible stops. if we want more people to use mass transit, surrounding cities and towns need to think about pedestrians more and design for them. Rt. 9 I'm looking at you. (Take a look at Fresh Market mall area... it screams foot traffic not welcome).

... said jake on Mar 19, 2018 at 10:54 AM | link

Last year Massachusetts moved away from toll booths, instead opting for EZ-Pass with plate scanners. Cars move freely through the system. No stops, no delay, no need for booths.

Why aren't tolls part of the discussion on 787?

The City of Albany would prefer to boulevard it, get back taxable land, improve access to the waterfront. NYSDOT cannot keep up with a $900m maintenance budget. More than 50 bridges to maintain and inspect?

The people who live with it don't want it. The people who don't use it don't want to pay for it.

Why can't there be an option considered, utilizing the same tech mass employs, to put tolls on 787? If it's so important to people to keep this white elephant standing - then perhaps the State should stop subsidizing it and start charging user fees.

... said Anonymous on Mar 19, 2018 at 4:29 PM | link

Anonymous - tolling existing facility which is paid for with taxes is not legal. Building more lanes would allow those lanes to be tolled, and that is being done in many locations. However building new lanes is not really practical for 787, nor there is sufficient demand for those lanes.

... said Mike on Mar 19, 2018 at 8:56 PM | link

@Mike,

It is not illegal. Connecticut is considering the same for their interstates. The feds have left it to states to decide if they want to implement this. Tolls are part of the reason 87 north developed and 87 south did not. The absence of tolls north and on 787 is suburban subsidy. Why not consider user fees?

... said Anonymous on Mar 20, 2018 at 9:26 AM | link

Quote from FHWA:

Under Title 23 of the United States Code (Highways), there is a general prohibition on the imposition of tolls on Federal-aid highways. However, Title 23 and other statutes have also carved out certain exceptions to this general prohibition through special programs. These programs allow tolling to generate revenue to support highway construction activities and/or enable the use of road pricing for congestion management.

... said Mike on Mar 20, 2018 at 1:41 PM | link

State needs $900m to keep this white elephant humming. DOT is not an authority, cannot raise the funds itself. This is going to continue to suck them dry. Interstate System Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Pilot Program is one such program the state could be looking into. The FAST Act gave states the flexibility to work with FHWA to implement a program such as this, granting them the the authority required for the project to proceed. This is something I'll be advocating to the MPO and our state representatives to look into.

... said Anonymous on Mar 22, 2018 at 2:06 PM | link